ANNOUNCEMENT: There will be a special event at my workplace, the MRC/CSO Social and Public Health Sciences Unit, running at 5PM on 7 February 2020. Dr Shuzo Sakata of the University of Strathclyde, Shogi player and teacher, will be showing us all how to play Shogi! Sets will be provided — please RSVP to me directly if you plan to come, to ensure we have enough sets.

What is Shogi?

Shogi is the Japanese form of Chess, the ‘royal game’, in which two players vie to be the first to checkmate their opponent’s King — meaning their King is unable to escape capture on the next move. Many centuries ago, when the ancient ancestor of Chess called Chaturanga was developed in India, the game spread across Asia and Europe, spawning new variations in every region that embraced the game. Shogi is first recorded in the Heisei Era in ancient Japan — around the 11th century — where it rapidly developed into its own, unique take on the royal game.

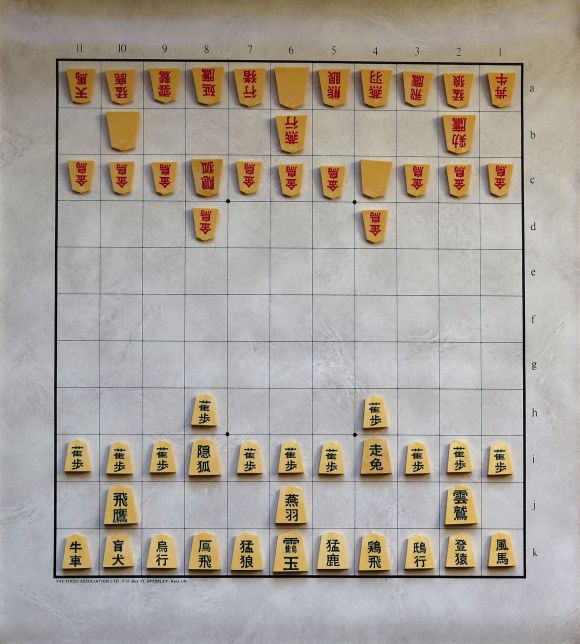

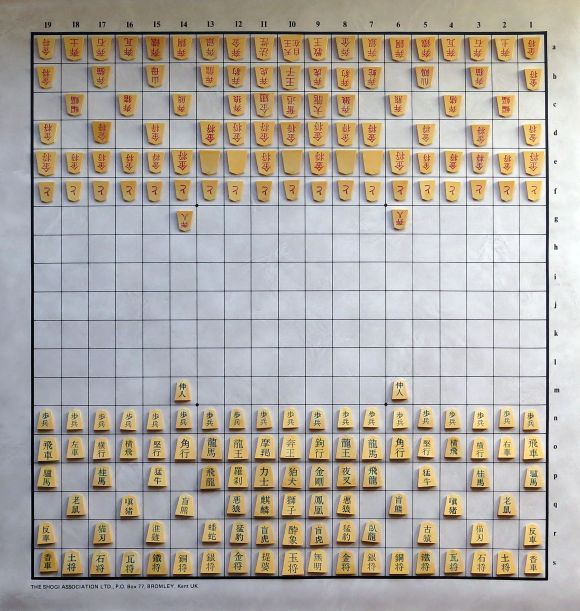

My traditional Shogi set — a Shin-Kaya board, with hand-carved pieces made from Japanese maple, with the kanji (Japanese characters) carved in the Minase calligraphy style in lacquer

How is Shogi different from Chess?

Shogi does share the same goals as Chess — checkmating the enemy King — and shares some of the same pieces. However, many of the fundamentals are quite different:

- The Board: a Shogi board is a 9×9 playing area of 81 squares, compared to the 64 squares of the chessboard. The board is not chequered either.

- The Pieces: Chess has six types of pieces: Pawns, Knights, Bishops, Rooks, Queens, and Kings. Shogi has ten: Pawns, Knights, Silver Generals, Gold Generals, Lances, Rooks, Bishops, Dragons (Promoted Rooks), Horses (Promoted Bishops), and Kings. Some of the shared pieces move differently, too: Knights make the same L-shaped jump but only forward; and Pawns move and capture only directly forward.

- Promoting Pieces: In Chess, pawns that reach the enemy’s back rank can promote to become a Knight, Bishop, Rook, or Queen. In Shogi, any piece that reaches the enemy camp (the three rows where their pieces begin the game) can promote. A promoted piece flips over, and the other side of the piece indicates their promoted form. Promoted Bishops (Horses) and promoted Rooks (Dragons) are the most powerful pieces in the game.

Shogi’s Ingenious Addition: Drops

There’s one major rule change that was added to Shogi in the 16th century and has come to define the game ever since: drops.

In Shogi, when a piece is captured, it is truly captured — it becomes the property of the capturing player. The capturer places the piece on a small side-board called a komadai (piece stand) and holds it in reserve. At any point from then on, they may forgo a normal move and instead drop a captured piece to any empty square on the board!

However, an important point to remember: promoted pieces, when captured, are demoted. Any dropped piece must be moved into the promotion zone again to be promoted. Two other key exceptions: Pawns cannot be dropped so that you have more than one of your pawns on a single vertical line; and pieces cannot be dropped in a space where they have no legal moves.

Drops make Shogi play and feel very different from Western Chess. Since captured pieces come back to life throughout the game, the number of pieces on the board stays roughly the same throughout — there are no endgame situations with near-empty boards, as in Chess. The constant back-and-forth of captures and drops makes a Shogi game dynamic, aggressive and fierce — attacks are frequent, and giving up the initiative to play defensively is risky.

Thanks to drops, Shogi is also much more decisive than Chess — less than 2% of professional Shogi games end in a draw, a staggering difference from the ~60% draw rate of professional chess!

Is Shogi hard to learn?

Not really! The biggest obstacle for most new players is learning the pieces — as you can see in the photo of my Shogi set above, all Shogi pieces are the same shape and colour, and the two players’ armies are distinguished by the pieces’ orientation (aim pointy bits at the enemy!). The different pieces have their names written on them in Japanese kanji characters, which are not so easy to learn for people who don’t speak Japanese.

However, the best way to learn is to simply dive in — after a game or two, the kanji fade away and are easy enough to recognise. I find it helps beginners to forget they are letters — this tends to prime us to try to divine their meaning, which makes them more intimidating.

Instead, just think of them the same way as you think of the shapes of Western Chess pieces — both are abstract shapes, and neither really relates to what the piece does or how it moves. The kanji are effectively just symbols, just like the odd shapes of Chess pieces. Also, you only really need to recognise the top characters on each piece — that’s enough to distinguish all the pieces from each other.

Other than that, it’s just a bigger version of Chess! The steepest part of the learning curve after that is getting comfortable with the powerful impact of drops — this is especially strange for seasoned Chess players, who will be accustomed to captured pieces playing no further role in the game. But again, given a few games, you’ll soon start to see the exciting, combative play allowed by the drop rule, and you’ll be chucking Gold Generals at your opponent like a pro.

How the Shogi Pieces Move:

Here’s a quick reference to the moves of the Shogi pieces:

As you can see, the King, Rook and Bishop move the same as in Chess. The Knight moves the same as in Chess too, but can only jump forward. The Pawn moves forward and captures forward — no diagonal capturing like in Chess. The Gold General moves one space in any direction except diagonally backward, while the Silver General can move one space diagonally in any direction or one space directly forward.

The promoted pieces are easy to remember — all promoted pieces move the same as the Gold General, with the exception of the Horse and Dragon. The Horse moves like a Bishop, but can also choose to move one square orthogonally; the Dragon moves like a Rook but can also move one square diagonally in any direction.

You might notice that the Shogi pieces have a general forward bias in their movement patterns, and most are short-range movers. This works very well with the drop rule — the combination of forward movement and drops favours attacking play, and the short-range movements prevent the game from becoming too chaotic, as it might be with powerful pieces appearing wherever they like on the board.

The flip side to this is that you can very occasionally have a condition called entering Kings, where both players’ Kings have moved into each others’ promotion zones. This makes it very difficult for anyone to win, as most of the pieces attack forward rather than backward. This is one of the few ways you can have a draw in Shogi. In practice this rarely happens, especially between beginners, who normally dive heedlessly into battle and neglect King safety entirely!

Note that the Horse provides a good reason for the Shogi board to not be chequered. In Chess your Bishops are confined forever to half of the board — either the black diagonals or the white ones. The Horse however can spend a move to shift from one set of diagonals to the other, so it’s less useful to have the chequers to indicate where the Bishops go — once promoted they can go anywhere.

Shogi: A whole family of amazing games

One of the things I love about Shogi is that, in a sense, it’s part of a whole game system rather than a single game.

To unpack that a little bit — you may be aware that there are many hundreds of Chess variants out there, variations on the game with different boards, pieces and rules. Shogi has these too, but unlike in Chess, many of the Shogi variants are hundreds of years old, and were refined over the centuries into fantastic games in their own right! Shogi variants are well-designed, well-balanced, and offer just as much intrigue and fascination as the traditional form of the game.

In fact, before the introduction of the drop rule made the modern game dominant, there used to be three variants of Shogi that were commonly played: Sho Shogi, or ‘Small Shogi’, which added drops later and become modern Shogi; Chu Shogi, or ‘Middle Shogi’, a much bigger game played on a 12×12 board of 144 squares; and Dai Shogi, or ‘Large Shogi’, played on an even bigger 15×15 board of 225 squares. Shogi used to come in Small/Medium/Large sizes! Alongside these main variations, there were numerous other variants of Shogi developed over the centuries, some of which I’ll describe below.

Today, besides Sho Shogi only Chu Shogi maintains a small presence — the Chu Shogi Renmei in Japan is the official governing body, and holds regular tournaments. This is unfortunate, really, as the Shogi variants are quite unique — particularly the larger variants, which are far larger than any commonly-played Chess variants, and offer hugely creative pieces and styles of play.

Thankfully, the efforts of one George Hodges in the late 20th century led to the revival of these ancient forms of Chess, and remarkably he even manufactured affordable sets for most of the large variants. Sadly George left us a few years ago, but his wife carries on that business, and she remains the only source on the planet for physical sets of most of the Shogi variants. I of course have bought several of them myself 🙂

Without further ado, here’s a brief intro to a few of the more spectacular Shogi variants — several of which I will bring with me to the Shogi event in a few weeks time!

Tori Shogi

Tori Shogi, or ‘Bird Shogi’, is an action-packed small variant of Shogi that packs a lot of action into its 7×7 board of 49 squares. At the start of the game, each player has 16 pieces in their camp — the board is more dense with pieces than in any other Shogi variant. To play you need to remember nine distinct piece movements, one less than normal Shogi.

Unlike most Shogi variants, which build on a common foundation of pieces that generally behave the same across many games, Tori Shogi uses an entirely new set of pieces named after birds (hence ‘Bird Shogi’). Instead of Pawns we have Swallows, we have Quails that move differently depending on which side of the board they start on, the King is now a Phoenix, and so on.

Like modern Shogi the game uses the drop rule, but with one major modification — in Tori Shogi you can drop a second pawn (Swallow) on a file where you already have one. In fact this is already happening in the start position, as you can see below! This rule heavily impacts Tori tactics, and also helps the board to not feel too constrained despite having so many pieces everywhere.

A Tori Shogi set from Angela/George Hodges — the top pieces have been flipped to show off their promoted forms. In this game only Swallows and Falcons promote. Note that the Swallows are in conflict right from the start of the game!

Tori Shogi is somewhat unusual among Shogi variants in that it was invented more recently — in 1799 to be precise. This means we have a fair bit more information on high-level play in this game than some of the others, where unfortunately top players’ games are lost in the mists of time. For Tori Shogi we have a few games from a tournament played between top-level Shogi professionals, some clever tsumeshogi (checkmate puzzles), and even a recently-updated English book on the game, The Way of Tori Shogi!

Tori plays in a very unique way, not just because of the small board and two-pawn drop rule, but also because the pieces are somewhat strange. The movements themselves are odd, but also the promoted Swallow turns into a Goose that moves in a bizarrely useless way (jumping one square diagonally forward left or right, or one square backward). Promotion is manda-Tori (sorry) in this game, so you have to have some clever plans afoot to use these weird pieces to achieve checkmate.

In any case, Tori Shogi is an exciting and unique game, and unlike some of the other variants there’s some good information out there on how to play well. I recommend picking up a set and a copy of The Way of Tori Shogi and giving it a go! Or just play with me, I already have a set 🙂

The moves of the Tori Shogi pieces. Clockwise from top left: Swallow, Falcon, Left Quail, Right Quail, Crane, Goose, Eagle, Pheasant, Phoenix.

Wa Shogi

Wa Shogi, or ‘Harmony Shogi’, marks our first step into the world of the larger Shogi variants played on boards bigger than the standard 9×9 grid. This game is played on an 11×11 grid of 121 squares, with each player having 27 pieces at the start of the game (compared to 20 in Shogi). To play, you have to remember 20 distinct movement patterns for your pieces (compared to 10 in Shogi).

Wa Shogi is an interesting beast — similar to Tori Shogi, Wa Shogi uses all non-standard pieces, and none of the pieces share their names with the standard Shogi pieces. Some do have equivalent moves to the standard pieces, but most are different. The pieces in Wa Shogi are named after animals — moving beyond just birds, as in Tori Shogi, we have fun stuff here like the Violent Wolf and the Climbing Monkey.

Not only that, but out of the initial starting setup for each player, there are only multiples of the Sparrows (pawns) — all the other pieces are different. That means there’s quite a few interesting tactical options in this game.

Wa Shogi is also unusual in that, unlike the other large Shogi variants, Wa Shogi was quite possibly played with drops. The game was invented after the drop rule became popular in 9×9 Shogi, and the Edo Era sources we have on Wa Shogi mention additional tactical options over the other variants, without specifying precisely what they mean; this could indicate the use of the drop rule. Additionally, some promoted pieces have identical moves, but are named differently and come from different unpromoted pieces; some suggest this indicates the use of drops, as dropped pieces are unpromoted so these cases would benefit from differentiating the promoted forms for ease of play.

Most modern players play Wa with drops, and the general consensus is that the game plays very well this way, so I definitely recommend using them. Wa Shogi is a fun change of pace from the traditional game, with the odd new pieces with weird moves and cool names, and the increased freedom of the larger board with drops adds a fun dynamic.

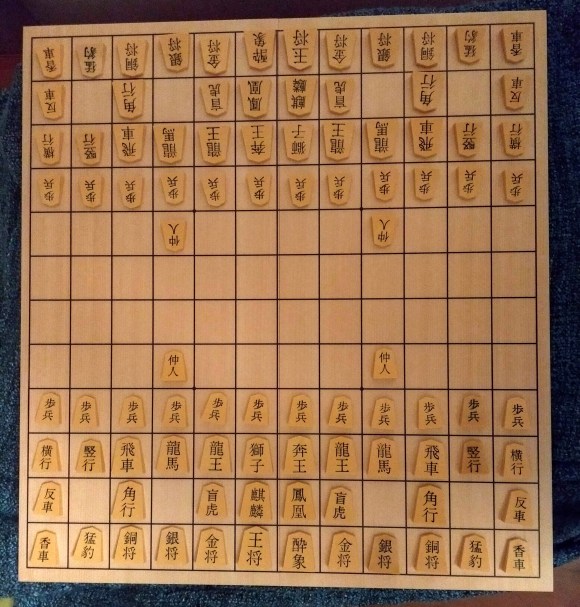

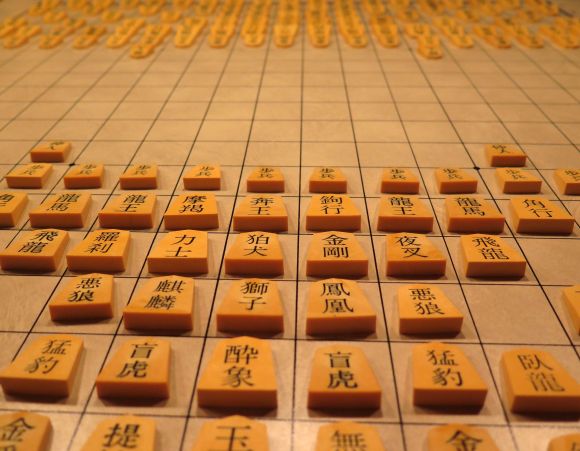

The starting setup for Wa Shogi, with the second player’s pieces flipped to show their promoted sides. Only three pieces don’t promote in Wa.

A closeup of the Crane King — in the centre of the bottom row — protected on either side by a Violent Stag (left) and Violent Wolf (right). Lot of violence going down in this game.

A move reference for Wa Shogi, included here mainly to show off the cool names for the pieces!

Chu Shogi

Chu Shogi is a spectacular game. Those lucky few who have played it frequently class it as one of the finest Chess games ever invented — and I thoroughly agree. The game is thought to have been invented in the 13th century and is one of the oldest forms of Shogi.

The game is not super accessible at first — the board is much larger than in Shogi (144 squares vs 81), and there are far more pieces on the board (46 pieces per player, compared to 20 each in Shogi). All told, you’ll have to remember 28 different piece movements instead of 10 like in Shogi! But the rewards are very much worth it.

Chu Shogi, like the other larger Shogi variants, does not use the drop rule — otherwise the games would go on far too long! Instead captured pieces are lost permanently, as in Chess.

Despite the large board and huge armies, Chu Shogi maintains a pretty swift pace. Each player starts with powerful pieces on the board from the beginning — including multiple Dragons and Horses, and the Free King which moves as a Queen in Chess. Interesting to note here that the Queen in Chess was invented three centuries later — Chu was an extremely innovative game for the time.

The most powerful piece, and the piece that defines Chu Shogi, is the Lion. The Lion effectively moves twice in one turn — it can make two consecutive King moves in any direction, with all that implies: it can capture twice; capture once and return to its starting square, appearing to capture without moving; or it can move once then return to its starting point, effectively passing its turn. All of these abilities are staggeringly powerful for different reasons. The Lion is so important and so engaging that the Chu community wisely added some rules to prevent players trading them off early in the game — it’s a bit complicated, but essentially you can’t sacrifice your Lion for your opponent to recapture unless you captured a sufficiently powerful enemy piece in the process.

Notably, Chu Shogi includes a piece called a Drunk Elephant, which moves like a King except it can’t move directly backward. This piece promotes to Crown Prince, which is a second King — and both Kings and Princes must be captured to win the game! Because of this, Chu and the other large variants with Drunk Elephants (most of them) don’t actually have a checkmate rule — any royal pieces must be actually captured to win the game. This allows you to sacrifice a Prince or King for tactical reasons — although honestly that’s rarely advisable!

At any rate, it’s a fabulous game, definitely worth your time if you’ve ever enjoyed a game of Shogi or Chess. It’s also the root of many of the larger Shogi games, meaning if you can play Chu it’s easier to jump up to the larger games afterward.

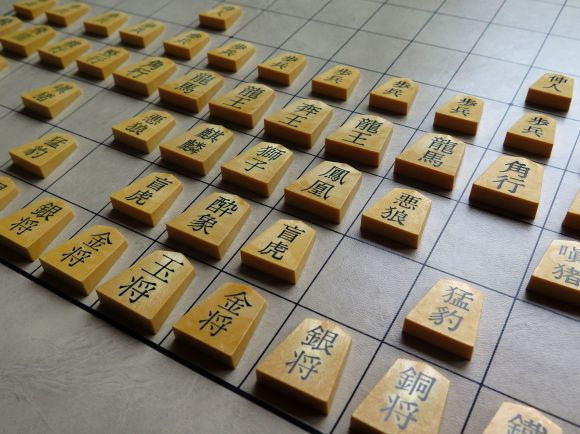

My Chu Shogi set, in the initial position. Board purchased from Aoyama Gobanten in Tokyo, pieces from Angela/George Hodges in the UK. The powerhouse Lion is two squares above the King, if you’re wondering.

The end of a Chu Shogi game — White wins after 288 moves (!), fittingly enough with a Lion checkmate. Check out the huge piles of dead pieces on the side of the board!

A rather spectacular Chu Shogi checkmate puzzle I found online — Black (bottom) to win in 3,257 moves! The puzzle is well-formed, meaning there’s only one possible solution. Good luck finding that one!

Dai Shogi

Dai Shogi, big brother to Chu, is much bigger than its sibling but not that much more complicated to learn. Essentially, take Chu, add eight more piece types with fairly easy-to-remember short-range moves, all of which promote to Gold General, and you have Dai!

Some criticise Dai as being too slow or not exciting enough, given that it’s essentially a scaled-up version of Chu with more pieces and a bigger board. But I strongly disagree — the larger board significantly expands the options available to players, the larger armies make the game more forgiving given the lower importance of material losses, and the powerhouse Lion is less dominating on the larger playing area. The game is indeed slower, but it’s also strategic, intriguing, and a great introduction to the larger Shogi variants given it’s easy to pick up once you know Chu.

A comparison of Dai Shogi (left) vs modern Shogi (right) — turns out that Large Shogi is, in fact, large

A close-up view of the King’s vast entourage in Dai Shogi. To either side he’s flanked by his faithful Gold and Silver Generals; to the front a Drunk Elephant and two Blind Tigers; then in front of those, dangerous beasts like the Lion, Kirin, Phoenix, Evil Wolves, Dragon Kings and more.

A Dai Shogi game I won online — after a mere 568 moves. Note my opponent threw a ‘spite check’ at me when he knew he was done for — even if I didn’t have checkmate on my next move, my Cat Sword (cool piece name) would’ve instantly recaptured his attacker anyway.

Tenjiku Shogi

Tenjiku Shogi — sometimes translated as ‘Exotic Shogi’ — is one of the most unique and dynamic games of Chess ever devised. The game is played on a massive 16×16 board (256 squares), and each player starts with 78 pieces in their army — and yet, the pieces are so powerful that the game can be over in less moves than a game of regular Shogi!

Like Chu Shogi is defined by the Lion, Tenjiku is defined by the Fire Demon. Each player starts with two of these. The Fire Demon can move as far as it wants in six directions — already extremely powerful by Shogi standards. Not only that, it can make a three-step area move — three consecutive King moves in any directions (but only one capture, for reasons that will soon become obvious). But on top of that, it burns everything it touches!

In other words, the Fire Demon instantly kills any piece adjacent to it when it finishes moving, meaning it can capture up to eight pieces in one move. Not only that, but if the opponent isn’t thinking and moves a piece next to it on his turn, that piece is also instantly captured — and that doesn’t count as your turn!

In addition to the two Fire Demons, your army also contains a Lion, five other pieces that can capture multiple times in a turn, two pieces called Water Buffaloes that promote to Fire Demons, and a number of range-capturing Generals — these are pieces that can jump over any number of enemy pieces in order to make a capture (each player has six of these). The upshot of all this is that, right from the opening, Tenjiku is a dynamic and dangerous game — attacks start immediately, and your huge 78-piece army starts dwindling very quickly. No other Chess variant plays like this, and it’s an absolute blast.

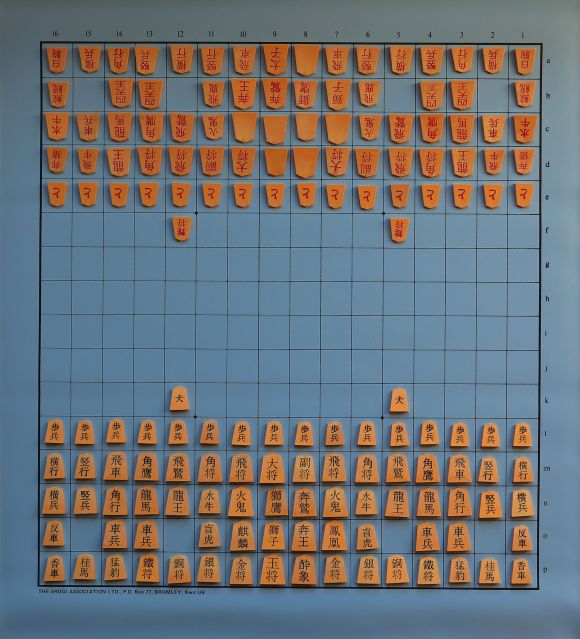

A Tenjiku Shogi set from Angela/George Hodges — the top player’s pieces have been flipped to show off their promoted sides. Of course I also own one of these sets.

Traditional Shogi lined up beside Tenjiku — just think how much damage one Fire Demon could do in that Shogi game!

A closeup of the deadly Fire Demon, ready to wreak havoc

Dai Dai Shogi

Dai Dai Shogi — or, literally translated, ‘Big Big Shogi’ — definitely fits its name. The game is played on a 17×17 board of 289 squares, with each player leading an army of 96 pieces! The starting setup, unlike most Shogi variants, is highly asymmetric — amongst the 96 pieces in your army, there are 64 different types of pieces, so many of your army are unique single pieces. All told, you need to remember 68 different piece moves — again unlike most variants, only 20 pieces promote in this game, and none of those promotions are to Gold General.

Dai Dai is quite a fascinating game, with a style of play all its own. This is the first large Shogi game to introduce promotion by capture — pieces promote as soon as they capture any enemy piece, and don’t have to wait until they reach the promotion zone. Promotion is also mandatory, whereas it’s optional in standard Shogi. This creates some intriguing tactical decisions, as some pieces effectively demote, becoming weaker when they make a capture — so you’d better make that capture count!

Dai Dai also introduces two powerful hook-moving pieces: the Tengu, or long-nosed goblin, that can make two consecutive Bishop moves at right angles to each other; and the aptly-named Hook Mover, which makes two consecutive Rook moves at right angles to each other. If that doesn’t sound so amazing, consider that a Hook-Mover on an empty board can reach any square in one move — hard to keep your King safe from that!

Dai Dai Shogi is well worth a try if you’re interested in a unique twist on Shogi — the asymmetric setup, huge piece variety and powerful hook-movers make for a surprisingly aggressive game, considering the size of the board.

Big Big Shogi indeed! Board and pieces from Angela/George Hodges once again.

Dai Dai Shogi set with the second players’ pieces flipped to show the promoted sides. Note how few of the pieces promote — not even the pawns!

The King’s entourage grows ever larger, and more diverse. Out of the 64 starting pieces, a full 47 of them are solo pieces, making for a complex and asymmetric starting position.

Maka Dai Dai Shogi

Maka Dai Dai Shogi is yet another step up in size from Tenjiku, played on a 19×19 board of 361 squares, with each player starting with an army of 96 pieces. The name is a bit interesting — ‘Dai’ means big or large, as we know, and ‘Maka’ is a word derived from Sanskrit that means something like ‘Superior’. So ‘Maka Dai Dai Shogi’ means basically ‘Superior Large Large Shogi’, or less awkwardly, ‘Superior Ultra-Large Shogi’. I would argue this is pretty accurate — it’s definitely ultra-large, and has a number of superior qualities.

One of the standout qualities of Shogi as compared to Chess is that most of the pieces can promote, and the large variants for the most part carry on this tradition. Maka Dai Dai, however, takes it to the next level, and allows the King himself to promote! A promoted King becomes an Emperor, the most powerful piece to exist in any variant of Chess: the Emperor can instantly teleport to any unprotected square on the board, including squares occupied by enemy pieces. In other words, the Emperor can instantly go anywhere and capture anything, so long as that square isn’t directly threatened with recapture by an enemy piece.

Alongside this, in Maka Dai Dai promotions occur by capture, as in Dai Dai Shogi — however here the promotion is optional, unless the captured piece is a promoted piece, in which case promotion is mandatory! This helps to speed up the pace of the game, as on such a large board reaching the promotion zone would take forever. Hook-moving pieces appear again in this game, but here they demote to Gold General on capture, so they’re effectively one-shot nuclear weapons if used to take out a promoted piece — use them wisely.

Promotion-by-capture also makes attacking the enemy King a risky proposition — if you mess it up, the King might capture an attacking piece, thereby immediately becoming an Emperor, which is both extremely powerful and desperately hard to checkmate!

“If you come at the King, you best not miss.”

–Omar Little

Maka Dai Dai, like most of the large Shogi variants, was invented by Buddhist monks — after all they have lots of time on their hands. This is more apparent in Maka Dai Dai than the other variants, as it includes pieces drawn from Buddhist mythology that behave in unusual ways. The Deva and Dark Spirit, for example, promote to Buddhist Spirit and Teaching King respectively — and any piece that captures them becomes a Buddhist Spirit or Teaching King, so these immortal creatures effectively never leave the board.

Substantial research has been done on this game by Professor Tomoyuki Takami, who states that Heian-Era sources suggest that Maka Dai Dai was actually one of the earliest forms of Shogi to exist, dating from as early as the 10th century. He says that the pieces of the game are inspired by Chinese astrology and traditional masked dances and festivals of the early Heian era, and that in the early days the game was played as a form of ritual rather than entertainment. Over the centuries, the game was reduced down to smaller forms, like Dai Dai Shogi, Dai Shogi and Chu Shogi, once they discovered that this ritual game was actually quite fun to play, but pretty long….

How long, you ask? Well, George Hodges once compared the lengths of various versions of Shogi — this is the number of total moves in an average game for each variant:

- Chess: 80

- Shogi: 110

- Dai Shogi: 400

- Dai Dai Shogi: 800

- Maka Dai Dai Shogi: 1100

- Tai Shogi: 2000

Wow, that’s long. If you start up a game of Maka Dai Dai Shogi, make sure you have the weekend free 🙂 I should say that I, of course, own a physical set for this game and would happily play it with anyone who asks. The board is too big for my table, however, so we’d have to find a place big enough!

A Maka Dai Dai set by Angela/George Hodges — promoted pieces on top.

Maka Dai Dai is such a large game that it can be quite intimidating — staring across the board at your opponent’s massive army lurking across the horizon feels quite different from more normal-sized Chess games.

The Mighty Emperor

Tai Shogi

OK, now this is getting ridiculous — Tai Shogi, or ‘Supreme Shogi’, is a spectacularly huge game played on a 25×25 board of 625 squares, invented in the 15th century by Buddhist monks (of course). Each player marches into battle with an army of 177 pieces each, and in order to play you need to remember 99 distinct piece movements.

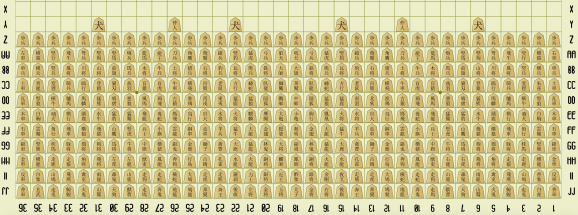

I’ve never personally played this, but remarkably, you can actually buy a set of this from Angela Hodges here in the UK. The board is more than a metre square! Even experienced players take upwards of two hours to set up the pieces in their initial position. As you can see below, each players’ starting ranks are absolutely chock full of pieces — in fact the opening phase is a bit like a sliding-block puzzle as you try to free up lines for your pieces to get into the action.

Notably, there are actually no Kings on the board — each player starts with an Emperor in play (!), and a Crown Prince that moves like a King. Both must be captured to win the game. Many of the other pieces have strong promotions, which occur by capture as in Dai Dai and Maka Dai Dai rather than by entering the promotion zone — so carelessly leaving pieces out to be gobbled up can rapidly turn the game against you!

Those who’ve played Tai say it’s an extremely challenging game, because it’s very hard to formulate any kind of sensible whole-board strategy in a game this large. As a result the game plays more like a wargame, with intensely tactical local skirmishes of great complexity breaking out across the board. Meanwhile, the everpresent Emperors make each move feel consequential — leave anything hanging and you may give the Emperor a chance to start some carnage. Given how old this game is, the creativity of all this is astounding — it’s kind of like an ancient version of Warhammer or something.

I don’t yet own this game but certainly plan to at some point — consider this a standing challenge to all! Once I get a set for this, I’m happy to give it a go with anyone who’s interested.

Regular Shogi just looks tiny compared to Tai Shogi! Without a doubt you could play an entire Shogi tournament in the time it takes to play one game of Tai Shogi.

A closeup of the Emperor’s immediate surroundings — quite a dense wall of protectors he has! The Emperor is at the centre of the bottom row, the Crown Prince (taishi) is directly above him, and the Drunk Elephant three pieces above the Prince.

Taikyoku Shogi

Unbelievably, Tai Shogi is not the biggest Chess game to ever exist. It used to be, until some documents were uncovered in 1997 with rules for a 16th-century Shogi variant called Taikyoku Shogi, or ‘Ultimate Shogi’.

This preposterous game is played on a 36×36 board of 1,296 squares. Each player has an army of 402 pieces, and to play you must remember 253 distinct movement patterns. Each side starts with a King and Crown Prince on the board, and a Drunk Elephant who can promote to Crown Prince — meaning you may have to capture three royal pieces to eventually win.

Unlike the other huge variants, in Tai Shogi promotion is once again by entering the enemy camp rather than by capture. Each army contains a huge variety of pieces with whimsical names like the Running Bear, Vermillion Sparrow, Violent Ox, Enchanted Badger, and — my favourite — the Vertical Puppy. If I ever play this game somehow, I’m going to devote my entire strategy toward devising a way to checkmate my opponent using the Vertical Puppy.

Amazingly, a real-life wooden set for Taikyoku Shogi was carved and used for a special segment on the Japanese variety show Fountain of Trivia back in 2004. Two Shogi pros faced off in a game of Taikyoku Shogi, using a little reference book to help them remember how the pieces moved. The game lasted 32 hours and 41 minutes, and ended in checkmate for the first player after 3,805 moves!

There’s a clip of the match on YouTube, unfortunately the quality isn’t great but the whole segment is there: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_c0Y26iTPSM

At the end of the match, the winning player says ‘I don’t want to do that again’; the loser says something hard to translate, but it’s kind of like ‘I have no regrets’, conveying the impression he doesn’t mind losing something so bizarre, and is mostly glad it’s over.

A closer look at one player’s setup in Taikyoku Shogi — imagine trying to remember all 402 of these pieces!

A fanmade version of Taikyoku Shogi — quite impressive!

Notes on the large Shogi variants

For much more detail on the Shogi variants, I recommend checking out this GeekList on Boardgamegeek.com from Shogi enthusiast The Player of Games that describes a large number of them. Numerous resources are linked there, and I borrowed a bunch of the images in this post from there as the photos the author took of his sets are far better than any others I could find. Many thanks to TPoG for taking the time to produce such crisp and high-resolution images of these great games!

Most importantly, TPoG’s list includes a detailed discussion of some discrepancies in the moves for certain pieces — the three main Edo Era sources for the larger games differ slightly in how they describe some moves. For the most part these differences are very minor, and in games this size aren’t really going to have any influence at all on the overall play.

However, the recommended changes in that list for the upgraded forms of the Lion make much more sense than the currently-available moves in the English versions of these games. They actually build on the Lion’s powers rather than weakening them. For reasons of consistency I highly recommend using the updated moves suggested in that list when playing Dai Dai Shogi, Maka Dai Dai Shogi or Tai Shogi.

Where do I go from here?

Well, as you can see, Shogi offers a whole world of interesting games. I wrote far too much here, and yet still didn’t cover anywhere near all the variants — there’s a number of smaller ones too, but I just love the big monster games. If you fancy trying a variant of Shogi, and want to pick just one, I’d recommend Chu Shogi — it’s monstrous without being ponderous, and the Lion is such a creative and beautifully-balanced addition to the game. Leaving aside my nerdy fascination with all things Shogi, it’s a genuinely delightful game. Tori Shogi is also a great choice, as it’s small and easy to learn but still has tons of depth.

If you want to dive headfirst into one of the monster games, I highly recommend Maka Dai Dai Shogi. It’s a fascinating game not just in terms of its unique play style and unusual pieces, but also because of its intriguing history and cultural relevance. When playing this game you can feel that it could have been a ritual experience, a rumination on Buddhist thought as well as a battle playing out on a (huge) chessboard. Sure, it’ll take awhile, and will require patience and dedication to get through a game — but those are quite Buddhist qualities, are they not?

Your best bet of course is to play modern Shogi — in my opinion it’s the finest version of Chess by quite some distance, and can easily support a lifetime of play and study. There are numerous places these days to play online, like 81dojo which is free, available in English and supports several variants as well. Obviously modern Shogi has by far the largest playing community of any version of Shogi, and rightfully so — it strikes a balance between complexity and simplicity that’s hard to beat.

For a taste of Shogi, come on down to our Shogi event next month and get acquainted with the modern game! I’m sure you’ll enjoy it, even if just as a peek into a corner of Japanese culture most of us never see. For those of you who really take a fancy to the game, you’re welcome to join Shuzo and myself in our soon-to-be-launched Shogi club, which will meet regularly in Glasgow to play Shogi and learn about the game.

And, if you’re a weirdo like me who can easily spend all day playing games, join me for a game of Tori, Chu, Dai, Tenjiku or Maka Dai Dai Shogi! Just make sure you free up your schedule first 🙂

Awesome! Now I know what you’ve been doing lately …🤣

I wish! Writing this was a nice break though

[…] I know the Shogi family very well, let’s take a look at some of Shogi’s power pieces (note that I won’t be looking at promoted pieces generally, since it would just […]

[…] some of you out there already know, I’m a huge fan of Shogi, the Japanese version of Chess, and its many variants. Shogi is a dynamic, attacking game enjoyed […]

[…] the meantime, I’m going to work in parallel on material for other historical Shogi variants. Today I’m going to introduce you to Dai Shogi, Chu Shogi’s big brother […]

You mentioned that there are tsume problems for tori shogi – could you point me to these? There are none in Hodge’s instructions (which include historical games) or in The Way of Tori Shogi.

I’ve only seen two of them, one is a mate in 19, then other is a rather cute 49-move problem that sends the King all the way round the board. You can find them in Ten Shogi Variants by George Hodges — http://katakas.org/documents/TSV.pdf

Is this PDF legit? Because the TSA sells this for 35 Pounds. If it is I’m quite happy.

[…] Had it been invented hundreds of years ago, I think today it’d be sat alongside Chess, Go and Shogi as one of the great traditional […]

[…] some of you may know, I’m a big fan of the large-board variants of Shogi, Japanese Chess. These enormous games extend Shogi out from its normal 9×9 board with 20 […]

[…] Shogi is here as a representative of the class of 13×13 Shogi variants. The only historic 13×13 Shogi variant is Heian Dai Shogi, which is a very early […]

Very interesting article indeed. Having spent 10 years in China I got interested in Xiangqi, which as you know is widely played in public places there – I have twice visited Japan but never had the chance to see a Shogi match, but I got Trevor Leggett’s famous book about Shogi and now I can play against the computer on the Nintendo Switch.

I don’t know how much you are interested in modern abstract games, but my feeling is that most of modern area-control games seem inspired by Go while most war games seem inspired by Shogi (drops and promotion of most pieces are indeed quite modern ideas for a 16th century game).

[…] the last few weeks, Stephen Tavener and I have been collaborating to bring Shogi and several of its variants to his amazing Ai Ai software, a general game-playing program that lets you play hundreds of […]

[…] Shogi — Possibly the greatest game ever invented by humans. The rules, piece movements, and aesthetics marry perfectly to create a glorious experience — a game of delicate beauty and intricate manoeuvre, combined with vicious tactics and constant aggression. I love everything about this game, and my Shogi board and traditional pieces with Minase calligraphy (pictured above) are perhaps my favourite gaming item in my home. If I could give this 11/10, I would. You know what, I’m going to, this is my blog, dammit! 11/10. (read more here) […]

[…] you’ve read this blog in recent years, you’ll be well aware that I consider Shogi one of the finest games ever created, surpassed only by its larger cousin Chu Shogi, which I […]

Oh Eric, I couldn’t be happier! This is great news. Give us a shout when you are up for a call.

Love you!!

Mum