I’ve been off work for a couple of weeks now, and rather than going on holiday I’ve mainly been trying to rest up after several months of really intense work. As part of my attempted recuperation I’ve been playing a lot of the board game Go, a game I have a tremendous fondness for but go through long periods of slacking off when my brain is busy with work stuff. I’ve been enjoying the opportunity to play more and thought that some of my friends and colleagues might enjoy the game too, so I decided to put together an intro to the game, alongside copious links to resources and ways to play online. I hope this might spur some of you out there to give it a try.

Go is a board game that’s been around for a very long time, and is generally believed to be the oldest board game still being played today; Go was invented about 3000 years ago in ancient China. The game is still immensely popular in Japan, China (where it is known as weiqi), and Korea (baduk), where professional play is well-established, and it boasts a growing following in America and Europe as well.

I’ll start by giving you a very brief summary of the rules of the game, then link you to some resources that will help you get started.

Playing Go

Go is known as a game of great complexity and subtlety, but the actual rules are simple. There are two players, White and Black, and each has 180 stones of the appropriate colour. Black always goes first, which confers a slight advantage, so in compensation White receives a bonus (komi) of 6.5 points at the end of the game (under Japanese rules, it’s 7.5 under Chinese rules).

The players start with an empty board of 19×19 squares, like so:

Notice that the board has nine marked star points which help players to orient themselves in this large playing space.

The players take it in turns to place a stone on an unoccupied point on the board. Once placed, a stone never moves, although it can be removed when captured. Stones are captured if all of the empty points surrounding them (their liberties) are occupied by stones of the opposing colour. This GIF shows an interesting example, where Black keeps capturing White stones only to eventually have his entire group captured himself by cutting off his own stones’ liberties:

Over time as stones are placed and some groups are captured or fortified, the players will sketch out and secure territory where their opponent cannot play without being captured. At the end of the game, both players total up the amount of territory surrounded by their stones, add in the number of stones they’ve captured from their opponent, and compare the totals (plus the 6.5 points komi for White) — the player with the highest total of territory and prisoners wins the game.

Below is an animated gif showing an example of play: a complete record of the famous ‘Game of the Century’ between Go Seigen (Black) and Honinbo Shusai (White). In this match players could adjourn to think at any time, so this game dragged on for three months! White won by two points in the end and the game is celebrated for some brilliant moves and fierce fighting over territory.

You can download a huge archive of 48,000 historic Go games in SGF format here, or if you want to view records of professional games in a handy web applet you can check out GoKifu.com.

The Style of Play

From the simple rules of Go, very complex patterns of play emerge. Unlike other prominent competitive board games like chess, in Go the board starts empty, and the number of available points to play a piece is very large (361 points on a Go board vs 64 squares on a chess board). The sheer number of possible moves is so huge that players must rely on intuition, a solid grasp of fundamental principles of play, and keen awareness of their opponent’s movements to play well.

This reliance on intuition makes Go a surprisingly emotional game — pick up any book by a serious professional and you’ll see them speak with great passion about how various moves and games made them feel. This in turn leads to some seriously intense contests — watch professional matches and you’ll see the players’ faces often contort with pain as they confront a powerful move by their opponent.

As a result of the complexity of the game, you’ll see Go players start their play in the corners and edges of the board — this is because it’s easier to make territory on the sides and corners, since you can use the edges as boundaries for your territory. As the sides and corners are decided, players begin reaching toward the centre of the board, attempting to connect their strongest groups of stones together and grasp larger chunks of territory.

The beginning of a Go game is often overwhelming for new players, who struggle to figure out where to start placing stones on this massive empty board. Generally the Black player will start play on the upper-right star point, which is considered polite to your opponent — it’s close to their end of the board and gives them a clear idea of where to start play. This helps somewhat, but the opening is still the toughest part of the game for newcomers.

As a result, most experienced players recommend that new players start on a smaller board, either 9×9 or 13×13. These are less intimidating to start with and get you into territory fights right away, giving you an immediate introduction to the moment-to-moment tactics of Go. Just bear in mind that you should try to advance to the full 19×19 board as soon as you can, as it’s a very different game at that scale. On the full board strategy becomes as important as tactics, and stones in distant corners have powerful implications elsewhere as patterns of territory shift and evolve over large swathes of the board.

Learning the Game

Learning Go is a long process, as the game requires an understanding of a lot of complex interactions between stones. There’s also a bit of a language barrier, as many Go terms derive from Japanese and are difficult to translate, so most players just use the Japanese words. As a result you’ll need to understand things like what it means when stones are in atari (stones that will be captured on the next move unless you do something to save them), or in seki (opposing groups of stones that can’t capture one another without endangering themselves).

Luckily there are some great introductory books I can recommend that will give you copious examples of these terms and many helpful and illustrative Go problems (tsumego) to test your skills.

For complete newbies I highly recommend Go: A Complete Introduction to the Game by Cho Chikun. Cho Chikun is one of the greatest players alive today, being the only player in history to hold all four main Japanese titles at the same time. His book is surprisingly short but very dense with helpful illustrations of key go concepts, and it rewards deep study and playing out the examples on a real or computerised board to experience each pattern for yourself.

From here you can check out the Elementary Go Series from Kiseido Publishing. This series covers key concepts of the game in detail in each volume. Many players recommend these books for players seeking to advance to intermediate levels of play.

When you’ve fully digested all this, you can try Lessons in the Fundamentals of Go by Toshiro Kageyama. This book is thicker than the others and quite dense with content — expect getting through this to take weeks, not days. But the concepts he explores are critical to good high-level play, and if you master them you’ll be well on your way to a thorough understanding of the game.

For online resources, I recommend studying the games of great masters, which you can easily find via the archives linked above and at places like GoKifu.com. The LifeIn19x19 forum is a great place to get tips from other Western players, with many members happy to give guidance on your development as a player. Finding good software is also key to learning the game, as this will be how you view and study the games of great players, or analyse your own games to examine your own strengths and weaknesses.

Go Software

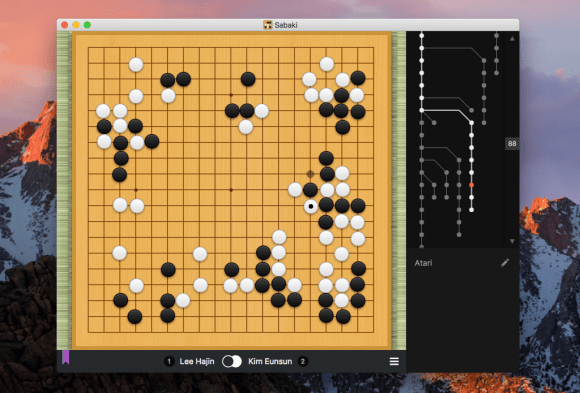

This section will be relatively short, because in my view there’s really just one piece of software you really need to study Go, and that’s Sabaki. Sabaki is free, open-source, and works perfectly on Windows, Mac and Linux. It also nicely captures the austere aesthetics of the game, showing you a lovely 19×19 wooden board sat on a tatami mat and simple black and wide stones. You can customise the look with themes as well, if you like.

A subtle touch that I really appreciate is that each stone is placed with a slight random touch, rather than precisely on the relevant point on the board, giving the whole thing a slightly more organic look as the game evolves.

Looks aside, Sabaki is a great piece of Go software, allowing you to view SGF files (the move-by-move records of Go games, as in the archives linked above), edit your own, and play against any AI Go engine that supports the GTP protocol (basically all of them). In particular I recommend using Tencent’s PhoenixGo engine, which is very strong and comes with instructions on how to link it with Sabaki on Windows and Mac.

Here’s a screenshot, stolen from Sabaki’s GitHub page:

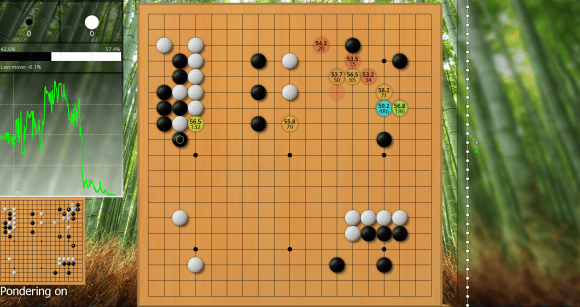

If you’re a more advanced user and want sophisticated analysis of your games from a strong AI, you can use Lizzie, which uses the Leela Zero engine to analyse your moves and show you what the engine recommends in each situation. Download the latest version from the Releases page at the link, then follow the instructions in the Readme file to get started. The results can be helpful, but bear in mind Leela Zero can only show us what she thinks, not explain why she thinks it, so still it’s better in my opinion to get input from human players and learn Go fundamentals rather than just ape the moves the computer engines recommend.

Here’s an example of Lizzie’s output, showing the user its recommended moves (the cyan-coloured one is Leela’s top recommendation):

Go Equipment

Go equipment, much like the game itself, is steeped in centuries of history and tradition. Japanese aesthetics in particular have had a profound influence on Go equipment. Today most high-level players or keen amateurs in search of fine equipment will go to Japan to get it.

The finest Go boards are made from the Japanese Kaya tree, and makers prefer that the tree is between 700-1000 years old when the wood is harvested. This combined with the fact that Kaya trees are protected in Japan means that true Kaya boards can be ludicrously expensive; free-standing boards with legs can rise well into the tens of thousands of pounds. Normal people go for so-called ‘Shin Kaya’ boards, usually made of Alaskan spruce, which looks close enough to the right colour and feel for most people and can be had for £100 or so for a tabletop board of 3cm thickness.

The finest Go stones, meanwhile, come from a place called Hyuga in Miyazaki Prefecture in Japan. The black stones are made of nachiguro slate stone, while the white stones are meticulously carved from clamshells, resulting in a beautiful shining surface striped with subtle lines. The finer the stone, the thicker it is and the denser and thinner the lines are. As with the Kaya boards, genuine Hyuga stones are incredibly rare and have price tags far beyond most mortals. However, these days you can get clamshell and slate stones made from imported Mexican clams that are nearly as perfect as the real thing, and a good set of decent thickness will set you back about £200-300 rather than tens of thousands.

Finally you have the Go bowls, which hold each player’s stones. Traditionally you place the bowls next to the board with the lid upside-down in front of it, and place any captured pieces in the upturned lid. This is polite to your opponent, who needs to know how many pieces you’ve captured as that affects the game’s final score. Go bowls again can cost ridiculous amounts for traditional Japanese wooden articles, but beautiful and functional bowls hand-carved from cherry and other woods needn’t set you back more than £150 or so.

The overall effect of a fine Go set should be a beautiful, smooth board with a soft yellow tone that perfectly compliments the black and white stones. When you place a stone on the board, it should make a satisfying ‘click’ against the wood — in particular on the free-standing boards, which have a chunk hollowed out of the interior to ensure it makes a pleasing sound.

In total, if you purchase a nice table Go set from a prized Japanese maker like Kuroki Goishi-ten, expect to pay about £300-400 for the lot (plus shipping/Customs fees of course). This is assuming a 3cm or 6cm Shin Kaya board, ‘Blue Label’ Mexican clamshell stones, and mid-level bowls of sakura wood or similar. Various distributors do sell some of their products in Europe — check Masters of Games in the UK, or Go-Spiele.de in Germany. Both stores also offer budget sets with Korean glass stones that are more than fine for most people; a set with a nice Shin Kaya board, Korean glass stones and Go bowls made with European wood should cost no more than about £200.

One of my great regrets from my time in Japan is that despite my intense desire for one, I never purchased a fine Go set for myself. They really are lovely. As a consequence of not taking that leap, I have this masochistic ritual of checking Kuroki Goishi-ten’s sales every summer, finding myself unable to justify the ~£100 in shipping costs on top of the cost of the set, and end up torturing myself over it for weeks. Someday I’ll take the plunge; in the meantime I do hope to get a Shin Kaya/glass stones set someday soon, and then eventually upgrade to proper clamshell stones.

Go vs Chess

For those of us in the West, the average person’s familiarity with abstract strategic board games often starts and ends with chess — even people who don’t play have probably heard of Garry Kasparov and Bobby Fischer. Both chess and go are intellectually challenging and stimulating, but they differ in quite fundamental ways. I’ll say up front that I enjoy both, and feel each one offers something the other doesn’t.

As described above, Go is simpler than chess as far as the rules go — stones are simply placed and never moved, and complex interactions between pieces arise from their configurations, not from the rules themselves. Meanwhile, in chess each piece moves, different types of pieces move differently, and the goal of the game is to trap the opposing king, which again depends on intimate knowledge of the roles and movements of the different major and minor pieces.

For the chess player, Go can initially seem a bit incomprehensible. Chess openings have been so thoroughly explored by humans and computers that many experienced players play the first 10-15 moves essentially from memory (depending on their choice of opening), while in Go this vast empty board makes the opening phase really perplexing. Note that Go players also have opening patterns they study called joseki, but these aren’t overly necessary except at high levels of play, and in fact many pros discourage new players from studying them until they’re quite advanced in their play.

The smaller boards and armies of chess mean the game also turns much more on tactics than Go. Chess does have lots of strategy to it of course, but on the whole it’s more likely that a single move can change the course of a chess game than a single move massively changes a Go game on that huge 19×19 board. So, if you’re more interested in intricate tactics and moment-to-moment attacking play, chess may be more your game; whereas if you’re interested in sweeping strategic movements and more intuitionist play styles, Go may be for you.

Honestly though, I’d say just play both — each game is rewarding in its own way, and I suspect a strong tactical chess background will serve you well in Go, just as strong strategic instincts in Go should surely help your chess game. I also recommend trying chess’ East Asian cousins Shogi, Xiangqi and Janggi. Shogi (Japanese chess) allows captured pieces to re-enter the game on the capturing player’s side which creates an interesting dynamic feel. Xiangqi (Chinese chess) has unique pieces and a larger board with territorial restrictions; Janggi (Korean chess) is very close to Xiangqi but with some rules differences that make it a very interesting variant. In fact I may post about these games someday down the line, as all are very accessible now with free apps for online play, and both Shogi and Xiangqi have some excellent English-language resources available (less so Janggi).

Playing Go Online

Speaking of online play, Go is likewise more accessible than ever thanks to the efforts of an extremely dedicated global community of players.

There are a number of great free services that enable online play against opponents all over the world, 24/7/365. A few of them specialise in real-time games, in which you and your opponent finish the game in one sitting, while others focus on correspondence games, where you take your time with each move and update the game on the server when you’ve chosen your move, and games take place at a leisurely pace over weeks or even months.

All of these services are free, by the way, though some offer subscriptions with extra benefits.

Real-Time Servers

IGS (The Internet Go Server) — By far the oldest of the bunch, the IGS has been around since 1992 (!). It started in Japan and still has the largest Japanese player community; many professionals play here. A nice software client, CGoban2, is available for all major operating systems, and there’s a good app as well for Android and iOS.

KGS — Popular with Westerners, KGS is well-known for being a chatty server where more experienced players will offer learning games for newbies and analyse your games to help you improve. Has lost popularity somewhat in recent years and the Android app is apparently a bit unreliable, however. I’ve heard some players recently recommending people shift to other servers, as they have difficulty finding good opponents here nowadays.

TygemBaduk — A Korean server but has an English-language website and client. Quite popular and apparently a good place to face strong opposition, though the client only works on Windows and iPad so be aware of that. The web client will work on any platform, though.

WBaduk — A very large Korean server, immensely popular. Another great place to face strong opposition, but they’ve also got problems with accessibility — just a few days ago the English client disappeared off the Google Play Store (!). Worth joining once you’re ready for strong opponents, but perhaps worth keeping on eye on things to see whether some changes to the service might be forthcoming.

Fox Weiqi — An absolutely massive Chinese server that’s becoming increasingly popular among Westerners due to having an English-language client and a polished Android app. Do note however that you have to sideload the app onto your Android phone, presumably due to China not really being a fan of Google services. Also the app is in Chinese only as far as I can tell. I’m installing the app as I write this so we’ll see if I can manage to find what buttons to mash to play a game with someone!

Correspondence Servers

Online Go (OGS) — A fabulous place to play correspondence Go. Uses a constantly-updated, modern web interface with responsive design — meaning it works perfectly and looks great regardless of whether you use it on desktop, laptop, phone or tablet. At any given time there are tens of thousands of correspondence games going. Real-time play is also supported, but most players do opt for correspondence games.

Dragon Go Server — A bit old-school design-wise, but has been around a long time. I’ve never personally played here but my impression is the userbase is pretty loyal. The web interface works fine for what it is, but definitely miles behind OGS. For playing on Android you can use a free plugin for the Go app BW-Go.

Go Apps

AQGo — An Android app that lets you play against the super-strong neural-net go bot LeelaZero, which is a community attempt to replicate Google’s super-powerful AlphaZero go bot. Needs to be sideloaded onto your phone.

Crazy Stone Deep Learning — A beautifully polished Go app that lets you play against a strong neural network opponent. The Pro version is a bit pricey as apps go (£12.99), but it’s been worth it for me to have an ever-present strong opponent that will analyse my games in-depth. Also available on Steam for a much higher price but also has a stronger rating (7-dan).

GridMaster Pro — A cheap, no-frills Go app that lets you play against a variety of Go engines, including Leela Zero. A slight caveat here in that in my experience, sometimes Leela Zero will refuse to make a move until I forcibly shut and reopen the app, but your mileage may vary. Leela and other engines can be downloaded directly through the app and installed instantly — check the app’s website for details.

TsumeGo Pro — An app for tsumego problems, Go puzzles that test your knowledge of key Go concepts. Extremely useful for polishing your skills and furthering your understanding of the complexities of keeping groups of stones alive — or killing your opponents groups! In-app purchases get you more problems to solve.

Pandanet IGS — The app for the Internet Go Server above. Free and works really well in my experience.

Well, that’s quite enough for one day — I hope this info might prove useful to someone out there who’s curious about Go. It’s a wonderful game and more accessible than ever, so if you’re interested in giving it a try, just pick your choice of app and get in there!

Master of Go on iOS looks a lot like Lizzie and lets you play against or analyze using LeelaZero or OpenELF.

[…] an oft-cited example of this category might be Go — it’s certainly an elegant game, with rules that are easy to summarise yet a level of […]

[…] game plays kind of like a combo of Go and Hex — a certain Go feel is apparent in how important whole-board strategic vision is, and […]

[…] filled with tension, and clearly can be a ‘lifestyle game’ just like Chess, Go, Havannah, or Hex. I highly recommend trying it — the steep learning curve means it may not […]

[…] Had it been invented hundreds of years ago, I think today it’d be sat alongside Chess, Go and Shogi as one of the great traditional […]

[…] from a game called Rosette. Over the years, numerous designers have tried to transport the game of Go to the hexagonal grid, only to find that the reduced connectivity of each point (from 4 adjacencies […]

[…] board size has a strong impact on play in Permute, as it does in other territory games like Go. Playing Permute on 12×12 is similar to playing Go on a 9×9 board — fighting […]

[…] Go — The quintessential game of territory, one of the oldest games on the planet, and perhaps the most revered. What can I say about this game that hasn’t already been said? Go is staggeringly deep, tactically complex and strategically varied, and capable of making hours fly by as you end up completely absorbed in the infinite possibilities in front of you on that 19×19 grid. Many people praise it for its simple rules, but I tend to stay away from that characterisation; in theory, the rules are simple, but the learning curve is steep, so it feels anything but simple as a beginner. Go can take a while to reveal its character and richness to the newbie; beginners are often urged to dive in and lose 100 games as quickly as possible, as it takes a lot of bitter experience to grasp the basic concepts. But if Go does end up hitting the mark for you, you may well find it takes over your gaming life. 10/10. (read more here) […]