Welcome to part II of my series of posts about games, part of my mission to keep my brain busy while I’m on strike!

Moving on from the last post about Hex, this time we’re going to explore a whole series of connection games, each by the same designer and each a clear progression from the last. By the time we get to the final game in the series, we’ll see one of the more complicated and sophisticated connection games out there.

The Game of Y

First though, let’s start with something simple. In fact, this game is even simpler than Hex, which scarcely seems possible! Recall that in Hex, each player has a slightly different goal — both seek to connect across the board, but each player is connecting different sides.

In the Game of Y, created by Craige Schensted (who later renamed himself Ea Ea) and Charles Titus in 1953, players have the same goal — to connect all three sides of a triangular board made of hexagons. To sum it up:

- Players take turns placing one stone of their colour in any empty hexagon on the triangular board. Once placed, stones do not move and are never removed.

- The first player to connect all three sides of the board wins. Corner hexes count as part of both sides to which they are adjacent.

And that’s it! Winning connections spanning the three sides look kind of like the letter Y, hence the name. Just like Hex, Y cannot have draws, one player will always win eventually. The first player has a winning advantage here, as well, so using the swap/pie rule is recommended to alleviate this.

Y is sometimes thought to be even more elemental than Hex, given the greater purity of the win condition. In fact, Hex can be shown to be a special case of Y, but in practice the games are pretty distinct in terms of the tactics required.

Here’s a sample game I played against a simple AI on a triangular board 21 hexes on a side; I used Stephen Taverner’s excellent Ai Ai software that comes with a plethora of great connection games:

Y benefits from playing on a larger board, given the shorter distances between sides when compared to a Hex board.

One issue with Y is that, even more so than Hex, the centre hexes are very powerful. Whichever player controls the centre is very likely to win. Schensted and Titus developed a number of ideas for new boards that would reduce emphasis on the centre, and eventually the ‘official’ Y board became this interesting geodesic hemisphere:

This board reduces the connectivity of the central points, giving the sides and edges greater influence on play. Some theorise however that on this board basically every first move should be swapped by the second player, although I don’t believe there’s any hard evidence that this is true. Kadon Enterprises sells a lovely wooden version of this board, albeit smaller than the one above, with 91 points available for stone placement.

This board reduces the connectivity of the central points, giving the sides and edges greater influence on play. Some theorise however that on this board basically every first move should be swapped by the second player, although I don’t believe there’s any hard evidence that this is true. Kadon Enterprises sells a lovely wooden version of this board, albeit smaller than the one above, with 91 points available for stone placement.

UPDATE: Phil Bordelon reports in the comments below that the Kadon Y board is so small that the game feels like a trivial first-player win! So perhaps if you want to try this board shape, play the larger one on the Gorrion server, or print the larger pattern on a mat for face-to-face play. David Bush also wrote to say that he believes the geodesic Y board can’t be balanced with just the pie rule, and given his serious pedigree in the connection games world I think I will take his word for it! He also says that three-move equalisation can be a solution. In this method, one player creates a position with two Black stones and one White, with White to move, and the other then decides whether to play White or Black.

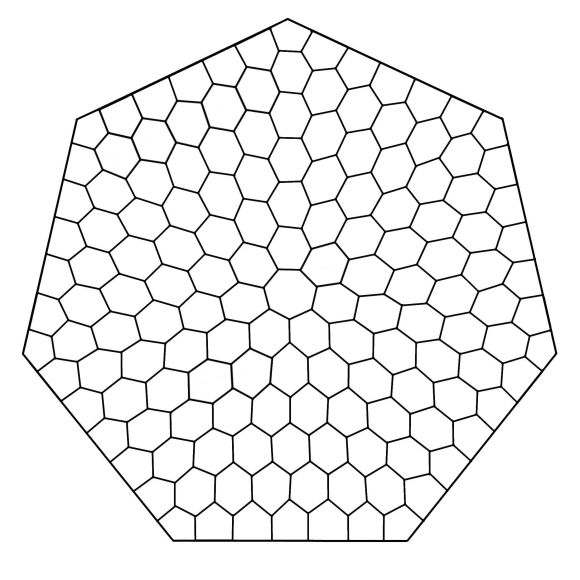

Another alternative option to the geodesic Y board is known as Obtuse-Y. In this version of the game we play on a hexagonal board tessellated with hexagons (a ‘hexhex’ board), with three pairs of sides marked — first player to connect all three of those marked sides is the winner. I like this version of Y since a large board in this format is more compact than a gigantic triangle of hexes, and it’s easier to have a balanced game than on the geodesic board. I made two boards for this version, which you can find on BoardGameGeek — a hexhex-10 (10 hexes on a side) and hexhex-12.

My hexhex-10 board for Obtuse-Y — connect all three colours to win! There are 271 playable hexes on this board.

In any case, Y is another simple-yet-deep experience and highly recommended. You can play against the AI using the Ai Ai software linked above, or against humans in real time via igGameCenter, or by correspondence on Richard’s PBEM Server. The geodesic version is only playable on Gorrion — definitely give it a try.

Finally, I want to note that Y has a ‘Misère’ version, much like Hex, where you try to force the opponent to connect all three sides before you do. This variant of Y is called ‘Y-Not’. I just love that.

Mudcrack Y and Poly-Y

The next step in Y’s evolution came when Schensted and Titus published a gorgeous little book called Mudcrack Y and Poly-Y (you can still buy it from Kadon), which contained hundreds of strange hand-drawn boards for Y players. They intended for players to use these boards by marking spaces with their chosen colour using coloured pencils. These weird little boards seem totally different from the normal Y triangle or geodesic hemisphere, and yet turn out to be topologically equivalent. Here’s a sample page:

A sample page of Mudcrack Y boards. Print them out, grab a couple of coloured pencils and give them a go!

As part of their continued quest to improve on the Game of Y, this book also reveals Poly-Y, a follow-up game intended to be a further generalisation of Y:

- Players take turns placing a stone of their colour on any empty space on the board. Once placed stones cannot move and are never removed.

- If a player’s stones connect two adjacent sides and a third non-adjacent side, that player controls the corner between the two adjacent sides.

- If a player controls a majority of the corners on the board, that player wins.

As you might have guessed, once again this game permits no draws (as long as you play on a board with an odd number of corners), so one player will always win. The pie rule is used to mitigate the first-player advantage.

Wikipedia and BoardGameGeek claim there is no ‘official’ Poly-Y board, but this isn’t correct. On the archived version of Craige/Ea Ea’s website you can find his summary of the history of Y/Poly-Y/Star/*Star, where he says this:

“Craige tried boards with more and more corners, 5, 7, 9, 15 … . At first it seemed that the more corners the better — there were more points to contest and a beautiful global strategic picture emerged. But as the number of corners increased, of necessity the length of the edges decreased. When the edges became too short it was found that it was too easy to make a Y touching 3 consecutive edges, thus “capturing” the middle edge and the two corners bounding it. This “edge capture” tended to make the game more tactical and local, focused on quick gains along the edge, thus losing the elegant global strategic flavor . So the strategic depth increased at first as the number of corners increased, but then decreased. Finally a board with 9 corners and 7 cells along each edge was chosen as the ideal balance…. Craige chose the 208 cell board with the 7-sided regions halfway to the center as the standard Poly-Y board.”

The same document has a picture of the standard board compared to two other candidates:

The ‘standard’ Poly-Y board is in the centre. The highlighted spaces on each board are the heptagons, required to allow the board to have 9 corners and still consist mostly of hexagons.

Here’s an example Poly-Y game won by Black on a board with 106 spaces and five corners — note here that the other player is Grey, and the yellow spaces are unoccupied:

Black controls the corners on the left side, and has blocked Grey from catching up.

While Craige/Ea Ea endorses the 208-cell nonagon as the best Poly-Y board, in Mudcrack Y and Poly-Y they also state the game plays well on any board with the following characteristics:

- Equal numbers of spaces along each side

- Mostly six-sided board spaces

- An odd number of sides (they prefer 5- and 9-sided boards)

Here’s sample 5-, 7- and 9-sided boards to print and play on:

5-sided Poly-Y board

7-sided Poly-Y board

9-sided Poly-Y board

Poly-Y is a clever game, and very deep; the win condition pushes players to extend their groups of stones all over the board, linking corners together through the centre to block the other player from securing their corners. The oddly-shaped boards are also fun to play on, and give the game a certain quirky aesthetic appeal. However, perhaps due to the rapid-fire iterations on Y produced by Schensted, Poly-Y never got the same level of recognition as Y itself.

Star

Schensted wasn’t quite done yet — far from it. His next invention was Star, which ramped up the complexity of the scoring system from Poly-Y and created a game that pushes players to connect all over the board. Star is another very deep game, and even on a small board presents a considerable challenge.

Star is played on a board of tessellated hexagons with uneven sides — in the sample small board below, you can see that three sides are five hexes long, and the other three are six hexes long; this ensures that there’s an uneven number of edge cells so that draws are impossible:

A small board for Star with 75 hexes and 33 border cells.

Here’s how to play Star:

- Players take turns placing one stone of their colour on any empty hex. Once placed, stones do not move and are never removed.

- A connected group of stones touching at least three of the dark partial hexes around the edge of the board is called a ‘star’. Each star is worth two points less than the number of dark border hexes it touches.

- When both players pass or when the board is full, the player with the most points wins.

- As per usual, the pie rule is used to mitigate the first player advantage.

This may sound a bit opaque, but the basic gist is: form as many stars as you can, but connect them together to maximise your points. The end result of a game of Star is an intricate web of connections snaking across the board for each player, attempting to connect and block simultaneously wherever possible. Since the entire edge of the board is available for scoring, the whole board interior tends to come into play as well, and unlike most connection games the board tends to be nearly full when the game finishes.

Unfortunately, despite pretty much universal praise for this game it’s very difficult to find sample games of Star, so here’s the only one I could find from Cameron Browne’s book Connection Games — I can’t emphasise enough that this is a great book that you should definitely buy!

In this example, the edge scoring cells are marked by X’s rather than a border of partial hexagons. Note that the completed game takes up nearly the entire board, and the pattern of connections formed is quite intricate even on this small playing area.

As with other connection games, playing on larger boards amps up the strategy. I found these boards lurking around the Wayback Machine, do give them a try:

This board has 192 interior cells and 51 border cells.

This board has 243 interior cells and 57 border cells.

I liked these boards so much that I made a range of Star boards — sizes 8, 9, 10 and 12 (the number being the number of hexes on the longer sides). I hope a few folks might print them out and give Star a try sometime.

My size 8 Star board in purple

Unfortunately, despite the coolness of this game it’s been thoroughly overshadowed by its successor; Star does appear to be playable at Richard’s PBEM Server, albeit only with an ASCII interface.

*Star

Finally we come to the last in the line of games spawned from our old friend the Game of Y. *Star takes yet another leap up in complexity, and to be completely honest, I don’t fully understand how this game works. This is partly because the instructions are written in what feels like an alien language — scoring refers to things called ‘peries’ and ‘quarks’ and it’s all a bit strange. However the abstract strategy game community praises this game nearly universally, so I remain keen to try and figure it out.

My understanding, questionable though it may be, is that the game essentially takes the core concept of Star — connect groups of edge-adjacent pieces together to maximise your points — to the next level by adding a scoring bonus for controlling corner spaces, and a significant scoring penalty (equal to twice the difference in the number of groups between the two players) for the player with the larger number of groups. This heavily incentivises the players to connect their groups, and the end result of this is some beautiful patterns of stones snaking across the board, as in these two sample games from the manual (one tiny one and one normal-sized one):

Here’s a closeup of that awesome board:

The *Star board. The centre star can be used by either player as a connection between groups — neither player may place their stones on it.

Note that the board has thicker lines to define smaller board sub-regions, which allows players to ease themselves into the full game. The game is popular enough to be produced in physical form by Kadon Enterprises, who make a wooden board set for *Star that I absolutely must buy at some point:

How cool is that! Someday I shall own this game, and I shall figure out exactly how to play it.

Luckily there’s a simpler game also playable on this board — Star-Y, where the players compete to be the first to complete a connection between two adjacent sides and one side not adjacent to either of those two. For *Star veterans there’s also Double-Star, where players place two stones per turn and the other rules remain the same; this seems like a small change but it significantly alters the play. New tactics and strategies are necessary to cope with the new threats that are possible with two stone placements.

So there we have it — a hectic journey from the elemental Game of Y through to the complex but highly-regarded *Star, courtesy of the brilliant minds of Craige Schensted/Ea Ea and Charles Titus. Craige/Ea Ea has stated that *Star is ‘what the other games were trying to be’, so from his perspective each game was improving on the last, and *Star is the best of the lot.

While researching and playing/trying to play these games, I’ve found that Star and *Star are frequently compared to Go, despite having connective goals rather than territorial ones. Given the much more flexible nature of the connective goals in these two games, I can see why — instead of connecting specific sides, players define for themselves the key parts of the board as they play. This is much more ‘Go-like’ in that the board is more of a blank slate, and does not inherently define the direction of play as much as in other connection games. So, if you’re a Go fan and skeptical of connection games, maybe try these two.

If you’re new to connection games in general, I’d start with Hex, then Y, then Poly-Y. You might enjoy Star and *Star more after trying some other games with more freeform connective goals, but with easier-to-grasp rules. I’d recommend maybe trying Havannah and Starweb for that purpose — and lucky you, they’ll be in my next post 🙂

I actually own the Kadon *Star board. It’s nice, but it’s made with a cheaper plywood stock than I was expecting, and my board came with a substantial chip. Somewhat disappointing.

Thread #404644 on BGG (I’m not posting the link so this doesn’t get eaten by the Anti-Spam Monster) has re-worded rules that make a lot more sense than the peri/quark nonsense that similarly turned me off of the game.

I need to play more Star; I think I’ve played it once. It feels like it’s right in my personal complexity wheelhouse, much like Havannah: more to it than Hex, but not a lot more complex to explain. I should also make some Caeth/Noc/Noeth boards for it, which is at least easy, assuming I don’t put the border in.

Aw, that’s a shame about the Kadon board! Shipping here to Scotland is rather expensive, so I’m not sure I can justify all that if the wood isn’t any good. It would cost about the same as my Shogi board which is really, really nice. Do you know if their Y board and Hex board are the same quality, or are they any better?

Thanks for the tip on the reworded *Star rules! Wow that is a lot better. I felt a bit ashamed of not comprehending the original rules, so I’m glad I’m not the only one 🙂

Very much agreed about Star — it’s got a lot going for it, and it’s such a shame it flies below everyone’s radar. In the hope of making it more accessible, I actually just made 4 boards for it in two different colour schemes, waiting for BGG to approve them — you’ll find them in the Google Drive folder of tons of stuff I’m about to send you! Feel free to use them for Caeth/Noc/Noeth versions if you like, of course. If you need SVGs I can provide those too.

The Y board is higher quality, wood-wise… but you don’t want it. I have it as well, and the board’s just too small; even with relatively casual play, the first player is pretty much always going to win (or the second, assuming you use the pie rule). Womp womp. If the sides were 3-5 spaces longer I suspect it’d be a more interesting game.

My Hex board is from Nestorgames, not Kadon, so I don’t know how theirs is.

Thanks for the boards!

Well that’s disappointing, but thanks — you’ve saved me a bunch of money 🙂 I may spring for the faux-leather *Star board at some point still.

I did kind of wonder about the size of that Y board. Shame they don’t have the option of a larger geodesic-style board, like you can find on the Gorrion server.

[…] is a clear descendant of Star/*Star, being a connection game that incentivises connecting certain key points on the board with as few […]

[…] yourself using some of the same basic concepts you might use in other connection games like Hex or Y — bridges and so forth. However Unlur is significantly different in one very important […]

[…] a game invented in 2017 by Craig Duncan — Side Stitch. Side Stitch is a game reminiscent of Star and *Star, where players must make connections between groups touching key cells along the edges of the […]

[…] forget — your own stones can be a liability! Unlike in games like Hex or Y, where having extra stones around is never bad for you, in Onyx carelessly-placed stones can help […]

[…] we have two fascinating variants of the seminal connection games Hex and the Game of Y. Odd-Y extends the core concept of Y to boards with more than three sides, while Pex transports […]

[…] during actual play. After that, we’ll take a look at another game, this time from the Game of Y, to see how Hex principles can apply in other connection games as […]

Hi. Irene Schensted taught me how to play Poly-Y at her house long ago. I wanted to give you a correction: Kadon’s version of the game of Y has 93 playable points rather than 91.