In keeping with Part II, today I’m going to introduce two games by one designer — Christian Freeling, who maintains an invaluable website full of his creations including versions playable in your browser. Christian has invented a tonne of well-regarded games over the years, and he has his own opinions on the most essential ones — namely Grand Chess, Dameo, Emergo, Sygo, Symple and Storisende. Although I’m not sure I can agree with most of them, personally speaking — that list is mostly games I certainly admire, design-wise, but don’t particularly enjoy playing.

However, there are two of his games that I find completely, indisputably brilliant: Havannah and Starweb. Both are fantastic additions to the connection game family.

Havannah

Havannah is a connection game that offers a completely unique take on the genre. Connection games are typically characterised by a sense of absolute clarity — the goal is simple, singular, and direct. Connect a thing to other things, and there you go. But in Havannah, players can win in three different ways — and to play well, you need to threaten to do all of them and defend against all of them simultaneously. The consequence is a game of intense depth and richness, and substantial challenge.

Here’s the basics:

- Two players, one with black stones and one with white, play Havannah on a hexagonal board tessellated with hexagons (known as a ‘hexhex’ board). The commercial Havannah release used a hexhex board with 8 hexes on a side (169 playable hexes), but Freeling considers a hexhex-10 board to be ideal (271 playable hexes).

- The game starts with the swap/pie rule.

- Each turn, a player places one stone of their colour on any empty space on the board. Once placed, stones do not move and are never removed.

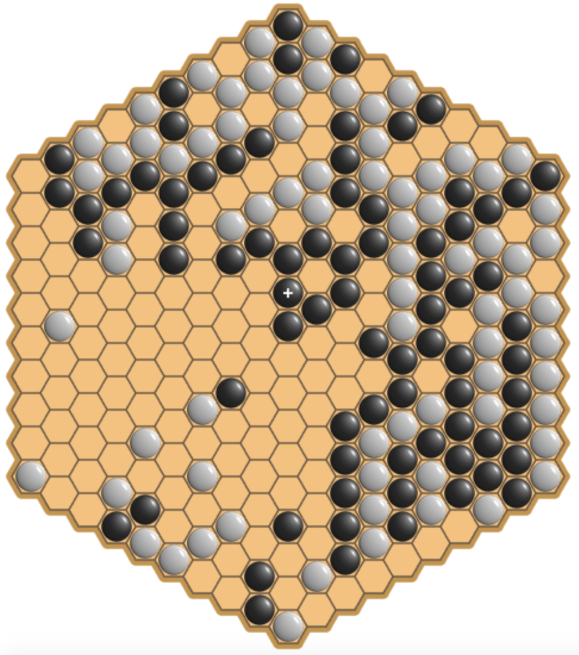

- A player wins when they achieve one of the following configurations (these examples are from real games on Little Golem) —

A ring — a chain of pieces that completely surrounds at least one hex, which can be empty or occupied (by opposing stones or your own):

Rings can get quite elaborate — can you see how White’s convoluted ring formation here?

Rings can also be tiny and enclose just one hex! These are easier to spot so it can hurt when you lose this way….

A fork — a chain of stones connecting three non-corner hexes on three different sides of the board:

Black completes a fork here. Note that it includes a corner hex, at the bottom, but also includes a non-corner one there too, so it still works!

A rather impressively labyrinthine fork here from Black. A clever win from what looks like a hard-fought game.

A bridge — a chain of stones connecting two corner hexagons:

White constructs a fairly convoluted bridge here from the top-right corner to the bottom corner

As you can see already, Havannah puts a lot on your plate as a player. The rules are hardly any more complicated than any other connection game, but the objectives are many and varied. The consequence of this is that at every turn you must be aware of the many possible implications of your opponent’s stones, and you have to learn to catch the signs of key strategic and tactical threats.

In fact the game is so strategically rich that in 2002 Christian Freeling instituted an AI challenge, betting €1000 that no computer could beat him even one game out of 10 on a hexhex-10 board within a decade. Predictably, he lost that challenge in 2012 and lost 3 games of his ten-game match against the machines.

Now one might feel disappointed somehow when computer players surpass humans in games, but honestly having superhuman AI for a newer game is a good thing — it accelerates the decades- or centuries-long process we normally need to really probe how our games hold up at a high level of play. That aside, to be fair to Christian Freeling, his game lasted nearly the full decade; these days, if anyone with some decent computing power is paying attention, any game would be lucky to last a few months. Especially now that AI doesn’t even need to know the rules first to master a game!

Basic Havannah Tips

Havannah, even more than other connection games, really comes alive once you’re armed with a few key strategic and tactical concepts. I’m by no means an expert here — at the end of this section I’ll link you to some people that are — but there’s a few tips I can offer to get you started:

- The game plays kind of like a combo of Go and Hex — a certain Go feel is apparent in how important whole-board strategic vision is, and that groups of stones can be ‘alive’ or ‘dead’ depending on their capability to form part of an attacking threat. The Hex side manifests in the moment-to-moment tactics and the importance virtual connections (bridges, in Hex terms) between stones.

- Perhaps the most important strategic concept to learn is the frame — a set of stones forming the backbone of an unbreakable winning formation, regardless of the opponent’s response. Check the guides I link below for some examples, and keep an eye out for your opponent threatening to make a frame!

- The one-hex ring enclosure — the mill — is a really important tool in Havannah. Rarely will you beat an experienced opponent that way, but building a mill can force a response from your opponent, gaining you initiative — and can interfere with their plans for their own stones, as well. Conversely, it’s important to learn how to defend against mill threats so you don’t fall prey to the same outcomes.

- Board size matters! On smaller boards, bridges and forks are powerful. On larger boards (hexhex-10 and up), bridges and forks are harder to build and rings become somewhat more prominent.

- Draws are possible in Havannah — but just barely. Out of tens of thousands of online games, there are single-digit numbers of draws that have ever happened! Therefore, don’t think an attempt at a drawing strategy will save you when things go bad — it’s extremely unlikely to work!

An example of a ring frame (Black) and a fork frame (White)

To really dig into the complexities of Havannah, I strongly recommend the brief but comprehensive guide by David Ploog, available in PDF format here (and please see his other amazing guides for other games in the BGG thread here), which covers all the key concepts and includes numerous examples and some problems to test your comprehension.

For a bit of discussion and strategic and tactical guidance for Havannah from the creator himself, do check Christian Freeling’s Havannah website, and his articles in issues 14, 15 and 16 of Abstract Games Magazine (that link takes you to their back-issue archives).

Finally, when you feel up to the challenge, you can play Havannah via Stephen Tavener’s Ai Ai program, the Mindsports website, on Little Golem, Richard’s PBEM Server, igGameCenter, and probably other places too! There’s a physical version of Havannah published by Ravensburger in 1981 that goes for very little on Ebay, but that only has a hexhex-8 board — for larger ones you’ll need to print something up yourself or repurpose another set, like Omega from Nestor Games.

While I’ve been on strike, my wife has helped me to learn Adobe Illustrator so I could make some nice hexhex-10 and hexhex-12 boards usable for Havannah and numerous other games. The final results are available in three colour schemes from the BoardGameGeek Havannah files section. These are sized for printing on 25 inch by 25 inch neoprene playmats, which are a popular way to get sturdy game boards made these days. If you printed them on mats of that size you can use standard 22mm Go stones on these boards.

I also made hexhex boards of size 7, 8, 10, 11, and 12 in the style of the board used on Little Golem, which is probably the most popular place to play Havannah. I like the random splash of colours across the hex grid, so I decided to create a range of print-and-play boards in that style. You can find these boards at my BGG filepage for Havannah along with the other versions.

Hexhex-10 board, with highlighted borders to allow players to use this one board as a hexhex-9, 8, 7, etc. as well. Two other colour schemes are available on BGG, too.

Hexhex-12 board in Little Golem style. I really am proud of this one, as it took some doing to replicate that colour pattern.

Showing off how the game works on my neoprene-printed hexhex-10 Havannah board. My dog Laika is fascinated.

However you go about playing it, Havannah is an absolute gem among the connection games. It’s tactical and strategic, mind-bending, and always enticing to play. If there were any justice in the world it’d be getting played by millions of people like Chess and Go, but alas, we’ve got to dig up players the old-fashioned way. But Havannah’s worth the trouble.

Starweb

One thing you’ll notice about Christian Freeling if you start following developments in the abstract strategy games community is that he has claimed he was retiring from game design about 100 times, yet he always comes back. Starweb appeared during one of these ephemeral retirements — he says the game came to his mind suddenly, basically fully-formed almost out of nowhere. Lucky for us that it did, as in my opinion it’s another masterpiece.

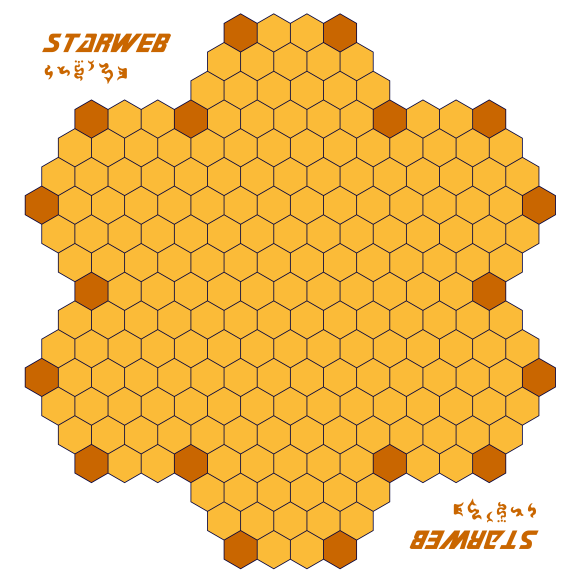

Starweb is a clear descendant of Star/*Star, being a connection game that incentivises connecting certain key points on the board with as few groups of stones as possible. What makes Starweb stand out is both the shape of the board, which creates 18 key corner hexes that drive the gameplay, and the triangular scoring mechanism.

Starweb’s simple and elegant rules lead to board-spanning strategic play, in some ways reminiscent of Havannah. Here’s what the standard board looks like:

Starweb standard board (dubbed size 10 in Ai Ai). It’s a hexhex-7 board with six added chunks of 15 hexes on each side, giving us 217 playable hexes in total, and 18 corner hexes (highlighted in brown). And yes, that is the font from Star Trek — bonus nerd points if you know what language that is underneath the Trek-style logo!

Play is appealingly simple, although the scoring mechanism takes a moment to sink in:

- Two players, Black and White, play on the standard Starweb board or one of its smaller variants. The board starts empty.

- Play starts with the swap/pie rule.

- Each turn, a player places one stone of their colour on any empty hex on the board. Once placed, stones never move and are never removed. Players may also pass their turn and not place a stone.

- The game ends when both players pass in succession.

- Once the game ends, players calculate their score as follows:

- Players identify each group of their stones that contains at least one corner cell (a ‘group’ is a connected bunch of like-coloured stones)

- The score for a group containing n corners is the sum of n and all positive integers less than n. In other words, a group containing 1 corner is worth 1 point; 2 corners = 2 + 1 = 3 points; 3 corners = 3 + 2 + 1 = 6 points; 4 corners = 4 + 3 + 2 + 1 = 10 points; and so on.

- The player with the highest score wins. In the event of a tied score, the player who placed the second stone wins.

So, to win Starweb, you have to occupy corner cells and connect those corners together into united groups of stones to score more points — the more corners in your group, the more points you score. At the start of the game the players will normally go back and forth occupying corner cells, and from there proceed to wind their way across the board trying to connect them together. This leads to dense, complicated webs of connected stones — hence the name Starweb!

I have to admit I’m not a huge fan of the second-player-wins-draws rule, since there’s already a swap rule in place at the start — that reminds me of Armageddon Chess, where Black wins in the case of a draw, which is pretty widely disliked. But the abstract games community generally seems very adamantly against draws, and designers tend to go to significant lengths to avoid them. That seems somewhat strange to me, since that means the game is by definition unbalanced as one of the players will have a winning strategy with perfect play; I personally slightly prefer Havannah/Shogi scenarios where draws are possible but just quite rare. In any case equal scores in Starweb are going to be pretty uncommon, so it’s not a big issue particularly, but the rule may influence your decision whether or not to swap your opponent’s opening move when going second.

Playing Starweb

The richness of Starweb becomes apparent once you discover that preventing your opponent’s connections between corners can be just as vital as connecting your own. Early on Christian Freeling realised that a minority strategy — in which one player declines to take all the corners they could and instead works to invade the opponent’s territory and deny them connections — is quite viable.

Here’s an example game against AI on a small board that he posted on BoardGameGeek:

You can see here that White (the AI) holds more corners (10 vs 8), but Black (Freeling) managed to cut several of them off, denying his opponent the ability to make big-scoring groups. Meanwhile he was able to slice through the centre of the board, leading to a winning score despite holding less corners.

This game also shows off other nice properties of Starweb: the games tend to be intricate and long; and the game plays well even on much smaller boards. The Starweb implementation in Ai Ai allows for boards even smaller than the above, and the game still holds up. It’s definitely more fun on the normal-sized board though.

The minority strategy still works on the large board, too:

After connecting stones 86 and 6 in the bottom right, Black will extend his lead by 5 more points. White is completely lost.

Freeling (Black) again takes less corners here, but manages to sprawl all the way across the board for a big-scoring connection. White has no hope of catching up, as the AI’s largest groups are split down the middle by Black’s connection across the centre of the board, and the extra White corners elsewhere are completely walled off.

Through these sample games we can see that Starweb admits a variety of strategic approaches; when first learning the game we might think grabbing every corner is essential, but as we see above, denying your opponent scoring opportunities can compensate. And by declining corners you can gain the initiative, exchanging turns you’d have spent on building a group for turns you can spend on attacking your opponent’s strategic goals.

At first the game might seem overly mathematical, in that counting corners and calculating scores seems so critical. But in actual play that doesn’t really interfere; once corners are occupied, you don’t need to track them anymore, and that normally happens very early in the game. Subsequently you just need to be aware of how many corners you need to connect to keep your opponent at bay. So the numbers come into play when planning your approach to a particular early-game board situation, but after that you can focus mainly on tactics and trying to connect your groups and execute your plan.

For detailed and enlightening discussion on Starweb’s strategic complexities, you can check out the discussion from Freeling and others on BoardGameGeek. That thread goes into more detail on the sample games I posted, and numerous others as well. There’s also some useful discussion on the Arimaa Forums in this thread, starting at post #104, although sadly the image links are all broken now. Starweb is still a young game, so as more people discover it perhaps we will see start to see guides on strategy and tactics on the level of those we can find for Havannah.

I highly recommend Starweb — you can play on Freeling’s MindSports site, or you can play against AI and human opponents on various board sizes via Stephen Tavener’s AiAi software of course. In my opinion it’s an underrated gem, right up there with Havannah as one of the most strategically satisfying connection games. It’s still early days for Starweb, as it was only developed in 2017, so hopefully as the years go by the game will develop the following it deserves.

Where next?

So, we’ve taken a look at the connection game titan Hex, the quirky and influential family of games by Craig Schensted/Ea Ea; and now two strategic masterpieces by Christian Freeling. Already you could easily spend a lifetime exploring these games and never unlock all their secrets.

Of course that’s far from everything the genre has to offer! Next time I’ll cover one more excellent connect-the-key-hexes game, Side Stitch, and then I’ll spend a fair bit of time talking about Unlur, an ingenious asymmetric connection game where the two players have different winning conditions.

[…] player must then try to form a loop of Black stones (a loop being defined here the same way as in Havannah), while White tries to prevent the loop from being formed. If Black forms a loop, they win; if […]

[…] you well here; for strategic considerations, you can take some inspiration from games like Star and Starweb. What’s key in Side Stitch, as in other connect-key-cells games, is to impede your […]

[…] filled with tension, and clearly can be a ‘lifestyle game’ just like Chess, Go, Havannah, or Hex. I highly recommend trying it — the steep learning curve means it may not be for […]

[…] designer Christian Freeling, whom I’ve praised extensively in this blog for his invention of Havannah and Starweb, two world-class strategic games, also invented numerous Chess variants over the years. Of […]

[…] back in Connection Games III: Havannah and Starweb, I praised designer Christian Freeling’s games but expressed a bit of skepticism regarding […]

[…] exciting for me was that Christian Freeling, a designer I’ve spoken about quite a bit in these pages, was immediately positive about the game. This meant a lot to me, not just […]

[…] does not use a balancing protocol like the swap rule we use in many other games like Hex or Havannah. Is the game balanced enough as-is, or does the first or second player have an advantage? […]

[…] so I made two variations of the *Star board to print myself. Superstar is a predecessor of Starweb, a fantastic connection game from Christian Freeling; Christian says Superstar is no good now and […]

[…] Havannah — I respect Christian enormously, but his decision to exclude Havannah from his ‘games that matter’ list is forever baffling to me. A classic by any measure, Havannah is easy to understand yet blessed with bottomless depth. The multiple goals create a sense of limitlessness that few games can muster. I can understand the impulse to push his fans toward his later games, and certainly he’s produced many great games after Havannah. But equally, there’s nothing wrong with getting it right the first time. Brilliant. 10/10. (read more here) […]