As some of you out there already know, I’m a huge fan of Shogi, the Japanese version of Chess, and its many variants. Shogi is a dynamic, attacking game enjoyed by millions of players around the world, and in my view is the most exciting of the major Chess variants played today. Chu Shogi is my favourite of the many larger variants of Shogi, and in my estimation is the best-designed game of the lot. I hope that by the end of this very long post you might be inspired to give this unique and fascinating game a try.

I have to admit that, as much as I love Chu Shogi, it is substantially more difficult to learn than modern Shogi or Chess. The board is large — 144 squares, as compared to 64 in Chess or 81 in modern Shogi — and each player starts with 46 pieces in their army. In Chess you need to learn the moves of six different types of pieces, whereas in Chu Shogi there are 28 different moves to remember!

However, once you get a game or two under your belt, all that complexity will melt away — you’ll be surprised how quickly the rules will become second nature. In this post I’m aiming to help you on that journey, by providing a complete reference to all the rules and piece movements you need to know to get started with this fantastic game.

I’ll start first with a brief look at the origins of the game, then I’ll describe the rules in detail, then I’ll show off the moves of all the pieces, and finally I’ll offer some basic tips for new players. Note that given the detailed kanji characters on the pieces and the complexity of some of the diagrams below, I’ve made this post so that each image links directly to a much larger version — please do click through to the larger images if any of the diagrams look a bit cramped on your device.

What is Chu Shogi?

Back in the 14th and 15th centuries, before modern Shogi existed, the Japanese were playing not just one, but three main variations of Shogi: Sho Shogi, Chu Shogi and Dai Shogi. These names mean, respectively, Small Shogi, Middle Shogi, and Large Shogi, and refer to the different board sizes used by each game: Sho Shogi is the direct predecessor to modern Shogi and is played on a 9×9 board; Chu Shogi uses a 12×12 board; and Dai Shogi is played on a 15×15 board. There were many other Shogi variants being developed in Japan around this time, but these three games were by far the most popular.

Chu Shogi is one of the most popular variants of Shogi played today, chiefly because of its finely balanced armies and the dominating presence of the Lion, a spectacularly powerful piece that shapes the entire game. A game of Chu Shogi is substantially more strategically and tactically complex than the smaller Chess-type games we’re used to, and offers the dedicated player limitless variety and challenge. Learning how to coordinate one’s army of 46 pieces on this large board can help us achieve greater strategic heights in our Shogi and Chess games, too.

Thanks to its fantastic play experience, Chu Shogi is the only ancient ancestor of modern Shogi that remains officially alive today. The Chu Shogi Renmei in Japan is the governing body for the game, and there are still regular tournaments happening. Here in the West, Chu Shogi has a small but die-hard following, and many Chu players consider it perhaps the best Chess-type game ever invented (I agree with this assessment). Nowadays Chu Shogi can be played online in real-time or correspondence forms, in domestic and international tournaments (albeit with only a few players), and solo against strong computer opponents. Chu Shogi is more accessible than ever, so why not give it a go?

The Origin of Chu Shogi

Chu Shogi’s immediate ancestor is Dai Shogi, which first appeared in the form of Heian Dai Shogi, a rather ponderous game played with 34 pieces per player on a 13×13 board. This game is first described in the diary of Fujiwara no Yoninaga, a high-ranking general, which was written between 1135 and 1155. Various other diaries throughout the 14th and 15th centuries make reference to Dai Shogi and present it as the most enjoyable form of Shogi, which suggests by this time it had reached its later form of a 15×15 game with 65 pieces per player (which is enormously better than Heian Dai Shogi).

The first reference I’ve found to a much larger form of Shogi comes in a mid-14th century text called Isei Teikin Orai. The book refers cryptically to a form of Shogi with 36 pieces on the board and a ‘dense’ form of Shogi with, apparently, 360 pieces. Unfortunately there are no further details in this book about this mysterious form of large Shogi, although perhaps it is a very early reference to some form of Tai Shogi with its 25×25 board and 354 pieces? Recent research by Professor Tomoyuku Takami proposes that, based on late Heian and Muromachi period documents, the first large Shogi may in fact have been Maka Dai Dai Shogi, which was then reduced in size to form the other large variants including Chu Shogi. More on this to come when I cover Maka Dai Dai Shogi in a future post.

The first detailed presentation of Chu Shogi’s board and rules comes in an Edo Period text titled Shōgi Rokushu no Zushiki (象棋六種之図式), which itself has a tangled history. The book was previously published by 16th-century Shogi craftsman Minase Kanenari as Shogi Zu (Illustrations of Shogi) in 1591, and he said it is a copy of a text he borrowed from a Kyoto Temple that originated in 1443. Allegedly that text is itself a copy of an even more ancient document, but we don’t know anything about that original source.

Below you can see scanned pages of the Shōgi Rokushu no Zushiki that show the Chu Shogi board, promoted pieces, and the movement powers of the pieces:

Thanks to this book we know that Chu Shogi existed in essentially its current form all the way back in 1443, and possibly significantly earlier. There are two other Edo-era sources, the Sho Shogi Zushiki and Shogi Zushiki from the late 17th century, which also describe the rules of Chu Shogi and numerous other variations of Shogi. In most cases they agree on the rules, but some of the very large games have some inconsistencies across these three volumes — more on that when I cover those games in future posts.

Regardless of some of the inconsistencies here and there, Shogi historians generally agree that Chu Shogi was a reduced form of Dai Shogi, which may have been the first large Shogi game or itself derived from larger games. Chu Shogi was then reduced further to Sho Shogi on the 9×9 board, and in the 16th century the drop rule was introduced, giving rise to the modern form of Shogi. Subsequently this rejuvenated version of Sho Shogi became by far the most popular form of the game. Prior to that, Dai Shogi was considered the most prestigious form of Shogi, followed by Chu Shogi, whereas Sho Shogi was thought to be a short and easy game more suitable for children (!).

After modern Shogi took over, Chu Shogi still remained mildly popular all the way into the 20th century. Unfortunately the game suffered a significant drop in popularity following World War II, and even strong support for Chu Shogi from some professional Shogi players failed to revive it to its former glory. In the 1970s and 1980s, an Englishman called George Hodges collaborated with Japanese Shogi scholars to bring Chu Shogi, Dai Shogi, and many other Shogi variants to Western audiences. George Hodges is largely responsible for popularising these games in the West, and he even produced physical sets for large Shogi variants all the way up to the gigantic Tai Shogi. Unfortunately George died in 2010, but his widow Angela Hodges continues producing his Shogi variant sets to this day.

The rules I’ll be presenting here are the rules used by the Japanese Chu Shogi Association, the Chu Shogi Renmei. While these differ in some respects from the rules generally used in the West, particularly in the promotion rules and King-baring rules, the textual evidence we have such as Chu Shogi checkmate puzzles indicates that the Chu Shogi Renmei rules are the same ones used in medieval Japan. For that reason I encourage you to use these rules, as they seem to be historically correct and also have less ambiguity in certain board situations.

The Rules

At the beginning of a Chu Shogi game, each player starts with 46 pieces of 21 different types. The initial board position looks like this:

Just for clarity, for the rest of this post I’ll refer to the two sides as Black and White — Black on the bottom of the board heading up, White at the top heading down. Note that some game records from a long time ago have Black at the top rather than the bottom, but this is always noted somewhere if that’s the case.

Winning the game

As in any Chess variant, the goal of Chu Shogi is to eliminate your opponent’s King. However, unlike Chess, in Chu Shogi you must capture the King, rather than checkmate it — and it’s possible to have two royal pieces at once in Chu Shogi, the King and a Crown Prince. If a player has both a King and a Crown Prince in their army, then the opposing player must capture both of those pieces in order to win.

The nature of Chu Shogi’s win condition means that there’s no stalemate as in Chess, and there’s no prohibition against moving a royal piece into check or checkmate. Obviously this is normally a pretty bad idea.

The Bare King Rule

The Chu Shogi Renmei adopts an additional rule where baring the enemy King is also a win; in other words, if you eliminate an opponent’s entire army except a King or Prince, then you win. However, if your opponent could on their next move bare your King as well, this is a draw, or if they could capture it on the next move, they win instead.

The rule further specifies that any endgame of King + some pieces versus a bare King is a win for the baring side, except when they only have a King + Pawn or King + Go-Between, in which case they have to promote the piece in question first in order to claim the win.

In practice the Bare King Rule isn’t hugely important, as most players would resign anyway as soon as the game seems hopeless, but nevertheless the rule has some interesting consequences for certain endgame situations.

Taking a turn

Once the game starts, Black moves first. The players alternate moving one piece on the board according to the specific movement powers of that piece. If that piece lands on a space occupied by an enemy piece, that piece is captured and permanently removed from the game (there are no modern-Shogi-style drops in Chu Shogi). Pieces cannot capture or move through friendly pieces. If a capture occurs then the move ends at that point — unless the capturing piece has ‘Lion Power’ (explained below), in which case a second capture can be performed. If the captured piece is the opponent’s last remaining royal piece (King or Prince), then the game ends immediately and the capturing player wins.

Normally a player must move a piece somewhere on their turn, but certain pieces with ‘Lion Power’ can ‘move’ without actually changing the board position — this means that player effectively passes their turn. This may be relevant in certain tight endgame situations where not moving can be preferable to moving.

Repeating positions

Sometimes during the course of play, players may enter into a cycle of repeating positions — for example, if a player is threatening their opponent’s King repeatedly with the same piece.

Chu Shogi Renmei’s rules have comprehensive guidelines for dealing with repeated positions:

- If the board position is repeating due to one player repeatedly checking the opponent’s King or Prince (placing them under immediate threat of capture), then they must change their move before the 4th repetition of the same position or lose the game.

- If one side is repeatedly attacking the opponent’s non-royal pieces during the repetitions, the attacking side must change their move before the 4th repetition of the same position or lose the game.

- If the position is repeating due to both players passing using ‘Lion Power’ pieces, then the first player who passed must change their move before the 4th repetition of the same position or lose the game.

- If the position is repeating and neither side is attacking, then a draw can be claimed.

- In cases not covered specifically by the above rules, then whichever side causes the 4th repetition of a board position will lose the game.

Generally speaking, due to the lack of stalemate and perpetual check thanks to the above rules, draws are rather rare in Chu Shogi.

Promoting pieces

Both players have a promotion zone on the board that consists of the four end rows of the board from their perspective (the rows that contain the bulk of their opponent’s army at the start of the game). So, Black’s promotion zone is rows A through D in the above diagram, and White’s is rows I through L.

If a player advances one of their pieces into their promotion zone, they may choose to promote that piece by flipping it over; the other side will have different characters written in red that show the name of the promoted piece. Promoted pieces are more powerful than the starting version of the piece — often significantly more powerful. Once a piece is promoted, it remains promoted until the end of the game. Promotion happens for each piece only once.

Here’s the starting position of Chu Shogi with all the pieces flipped to show their promoted sides:

Note that three of the pieces still have black characters on them — these are the King, Lion and Free King, none of which can promote. I’ve left them in these diagrams just as a reminder of their position in the starting array.

When a piece moves into the promotion zone, promotion is optional — this may sound pointless, but there are situations where promotion may not be advantageous, at least not right away. Some pieces have promoted forms with very different movement abilities, so you may wish to defer promotion if you could make better use out of the original movement pattern.

If you want to promote the piece later after deferring when you first entered the promotion zone, you have to either A) move the piece out of the promotion zone, then re-enter the zone and promote on that move, or B) capture something in the promotion zone.

Note that some pieces that cannot move backward — Pawns and Lances — could theoretically get to the last row on the board and never be able to move again. If an unpromoted Pawn is about to reach the last rank, you can promote it even on a non-capturing move; if any other piece gets stuck unpromoted on the last rank, it just sits there unable to move until it gets captured.

NB: I’m using the Chu Shogi Renmei promotion rules here, which are more strict than the rules on Wikipedia or in the Middle Shogi Manual. In those rules, you can promote any piece after a non-capturing move when already within the promotion zone. However, this makes a lot of Chu Shogi board positions a bit more ambiguous and can cause some rules questions, so I recommend the Chu Shogi Renmei rules.

The Pieces

Remembering all the different moves of the Chu Shogi pieces is a bit challenging at first, but you’ll soon see that there’s a certain logic and pattern to them. The vast majority of pieces can move in a few directions one square at a time, or over any number of squares in some directions, or some combination of the two. A few pieces can jump over some squares, even if those squares contain friendly or enemy pieces. A few others have ‘Lion Power’ and effectively move twice in a turn; this is explained further below.

I’ve made some handy diagrams to illustrate the moves of all the pieces. The diagrams show you the pieces in a rough order, starting from the top row of your army down to the last row. Each piece’s promoted form is shown below its initial form. Remember that the King, Free King and Lion don’t promote.

In the diagrams below, orange squares indicate squares a piece can step to during a move; squares with stars indicate squares pieces can jump to, passing over intervening pieces; arrows indicate directions in which the piece can move an unlimited number of squares; and finally, exclamation marks indicate the piece can perform igui capture on that square (see ‘Lion Power’ below). As always, click each picture to see a massive huge version of the diagrams.

You’ll notice a certain pattern to the distribution of piece movements in the starting position. The back rank contains the King, the Drunk Elephant (both a strong defensive piece and capable of promoting into a royal Crown Prince), and a large crew of short-range Generals. The second and third ranks contain mostly longer-ranged pieces, with the most powerful pieces sitting in front of the King. The fourth rank consists of 12 Pawns, and finally in the fifth rank we have two Go-Betweens, the spearhead of our advancing army.

Note that to help you remember the piece names in full, I’ve used two-character pieces in the above diagrams, but for some subsequent diagrams (and in future Chu Shogi articles) I’ll mostly use abbreviated, one-character pieces to aid visibility. Here is a zoomed-in view of one player’s army with one-character pieces; the first diagram shows the starting position again, and the second has all the pieces flipped to show their promoted sides:

- The starting position for one player, with one-character pieces.

- The starting position with all pieces flipped to show their promoted sides.

For players of modern Shogi, you’ll see that that in general there are many more powerful pieces in Chu Shogi. In Shogi the most powerful pieces are the Dragon King and Dragon Horse; in Chu, you have two of each these on the board at the start of the game, and when they promote they become much more devastating. In Chu you also have the Free King, sometimes called the Queen, which moves as far as it likes in eight directions just like a Chess Queen (but Chu Shogi invented this piece 250 years earlier!). Finally you have the Lion, a piece so flexible, powerful and exciting to use that it inspired me to write a whole article about powerful pieces in Chess variants.

Print versions: I’ve also produced two single-page reference sheets for all the Chu Shogi moves, one version with 2-kanji pieces and another with 1-kanji pieces. The pieces are paired up with their promoted forms and again mostly follow the order of the diagrams below. Hopefully these will help you out if you bring a Chu Shogi set to a games night or your Chess or Shogi club.

- Chu Shogi reference sheet (2-kanji pieces)

Lion Power

To understand how strong the Lion is, you need to understand its special movement rules, referred to as ‘Lion Power’. As you can see in the diagram above, the Lion can jump over one square in any direction, bypassing any friendly or enemy piece on that square. However, it can also do something uniquely powerful — it can perform two single-square moves in any direction in a row, on one turn, and one or both of these moves may be a capture.

This has some interesting side effects — for one, the Lion may appear to capture an adjacent piece without moving, by moving to its square, capturing it, then moving back to its starting square. This is called igui — Japanese for ‘stationary eating’ — and in the diagrams above the squares where igui is possible are marked by exclamation marks in the Lion’s diagram. The Lion may also move to an adjacent empty square and then back, appearing not to move at all; this is how one may ‘pass’ their turn, as mentioned above. Finally, the Lion may capture two pieces in one move.

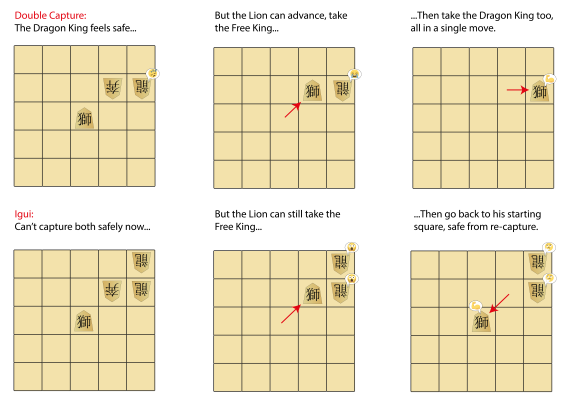

Here are a couple of examples of the Lion’s unique powers:

As you can see, these powers make the Lion far more flexible and powerful than any other piece on the board. No enemy piece can sit adjacent to it, as it will just be instantly gobbled up igui-style. The Lion can easily escape threats by leaping away or by taking two nimble steps around interposing pieces. Finally, if an opponent leaves multiple pieces undefended, the Lion will eagerly devour them all. So, even without long-range movement abilities, the Lion dominates the board — and when you use it yourself, you’ll see how exciting the game becomes thanks to this magnificent beast.

Lion-trading rules

Chess players out there will be familiar with the Queen trade — when two players mutually agree to simplify the board position by exchanging Queens. In a Queen trade a player will offer their Queen for capture by the other Queen, with their pieces in position to immediately recapture the opposing Queen. The end result is both players lose their Queen but nothing else of consequence, leaving behind a less tactically complex and usually more boring game.

However, the wise inventors of Chu Shogi knew they had a hit on their hands with the Lion, and wanted to discourage players from trading them off to simplify the game. To achieve this they included several anti-trading rules that forbid players from capturing or re-capturing opposing Lions in certain situations. These rules ensure that the Lions often stay on the board for a long time during a typical Chu Shogi game, and that gives this remarkable piece a chance to truly shine.

I’ve created a few diagrams here that summarise the main points of the Lion-trading rules:

These rules seem a bit complicated at first, but as you can see in the diagrams above, there’s really just a few points to remember:

- A Lion can always capture an adjacent Lion.

- A Lion may not capture a non-adjacent Lion protected by an enemy piece — this prevents a mutual Lion trade, where the Lions are off the board but the position doesn’t change much otherwise.

- If a non-Lion piece captures a Lion, then the opponent can’t do the same thing on the next turn. This means that if your opponent has just taken your Lion with a non-Lion piece, you can’t take theirs right away, even if it’s unprotected! This prevents trades making use of non-Lion pieces.

- A Lion can capture an opposing Lion protected by another piece, but only if it may capture another piece at the same time — and as long as that extra piece is not a Pawn or a Go-Between. This means that if both Lions are going off the board in this kind of position, the Lion that initiates the exchange has to take an additional piece of at least some value with them; again this discourages Lion trades, since trades won’t be possible on even terms.

There are some interesting tactical situations that can arise out of the Lion-trading rules, but don’t worry about those for now — when you’re just starting Chu Shogi, focus on simply exploring the Lion’s capabilities and getting used to these rules. In subsequent posts I’ll talk some more about these rules and how they impact Chu Shogi tactics.

Other pieces with Lion Power

Two other pieces in Chu Shogi have a limited form of Lion Power — the Horned Falcon and the Soaring Eagle. The Horned Falcon can use Lion Power only directly forward — so it may jump two squares forward, or make one or two forward steps, or make an igui capture or a double capture forward. The Soaring Eagle can do the same except on the two forward diagonals only.

The Lion-trading rules do not apply to the Horned Falcon or Soaring Eagle.

Note also that the Kirin (sometimes written Kylin in some Western sources) promotes to a Lion. Once the Kirin promotes to Lion, all Lion Power and Lion-trading rules now apply to that piece.

Beginner Chu Shogi Tips

Chu Shogi can seem daunting at first — just look at all those pieces! — but here I’ll give you a few key tips that can help direct your play in the first few games. I’ll write some additional Chu Shogi articles in the future, including detailed discussion of the opening, middlegame and endgame, and a fully-annotated game (this will take some time — the game I’ve chosen to annotate is 327 moves long!).

For now, here are some key tips for each stage of the game:

The opening

Chu Shogi games are long — expect a typical game to last about 300 moves (compared to an average Chess game at about 80 moves, or a modern Shogi game at about 120 moves). With that in mind, take your time in the opening — Chu Shogi games tend to build gradually, with each player re-arranging their pieces within their own ranks in preparation for launching a coordinated attack. Take your time, follow the tips below and you should be able to keep yourself out of trouble in the opening.

- Don’t neglect your short-range pieces! Chu Shogi has a lot of powerful long-range pieces, so it’s easy to forget about your short-range pieces in the back ranks. However, if you advance these pieces early on, they serve a valuable role in protecting your front-line Pawns from an enemy Lion invasion. Later in the game you’ll also have a much easier time promoting these short-range pieces if you’ve already advanced them early, and many of the short-range pieces have useful promotions. Finally, a coordinated march of Generals on the enemy position can enable you to shift the enemy’s long-range pieces into disadvantageous positions, disrupting their attacks or even exposing them to capture.

- Set up a solid defence around your King. Even with the many rows of pieces in front of your King, you still should spend extra effort to protect him right from the start of the game. In particular, keep the Drunk Elephant, Blind Tigers and Gold Generals close at hand — all three of these pieces can cover a lot of squares around your King. The Drunk Elephant becomes extra valuable if kept alive in the endgame, since it can promote to a Crown Prince and make your opponent have to capture two royals to win the game. Similarly, the Gold Generals promote to Rooks, which are extremely useful pieces to have around in the endgame when many other long-range pieces may have been swept off the board.

- Use your Lion to claim the centre. Jumping the Lion over your Pawn line early on to cover the centre of the board is very useful — it deters the enemy Lion from making opportunistic attacks on your vulnerable Pawns, while threatening to do the same to them. If your opponent starts harassing your Lion with capturing threats, you can easily retreat it back over the Pawn line to safety. The Lion controls a lot of space and is very hard to pin down, so use that to your advantage!

The Middlegame

The middlegame of Chu Shogi starts once both players have developed their short-range pieces behind the Pawns, lined up strong long-range pieces behind them, and are starting to attack the enemy’s position, often along one of the flanks of the board. Succeeding in the middlegame requires strong strategic acumen — tactics are important, but there are so many possible moves on any given turn that it’s often very difficult to anticipate the opponent’s replies to each of your moves. Solid strategic principles can guide you better over the longer term.

- Advance methodically. Concentrate your attacking forces along the side of the board where your opponent looks weakest. Back up Pawn advances with your short-range pieces, and keep long-range pieces behind them to snipe at any invading enemy Generals or to deter Lion incursions. Try to keep your pieces moving in lockstep — retreating weak pieces is slow and will lose you time, and time is a key resource in Chu Shogi.

- Avoid pointless material losses. At this stage of the game, try to amass your forces on weak points in the enemy camp, allowing for a mass assault later on, rather than impatiently trying to punch through with just a few strong pieces. Early material losses can mount up, and sacrifices can fail to significantly damage your opponent’s defences given the size of each player’s army; whatever hole you’ve punched in the enemy lines with your powerful piece sacrifice will soon be plugged by another piece.

- Don’t rush toward promotion. Your short-range pieces will take time to breach enemy lines and hit the promotion zone — don’t rush this, they serve a valuable role in the meantime defending your pawns and discouraging Lion invasions! Your long-range pieces can promote very easily once the board opens up after a few battles break out, so don’t fling them headlong into danger to seek promotion — soon enough you’ll be able to promote your long-range pieces essentially at will. Once you do start to make headway on the enemy position, try to make it a goal to promote a Vertical Mover to a Flying Ox — the Flying Ox is a strong attacking piece.

- Keep your Lion centralised and patrolling. Keeping your Lion in the centre will help restrict your opponent’s advance to one flank or the other, and will keep their Lion contained. While managing your own advance, don’t forget to keep an eye out for the enemy Lion, and look for opportunities to drive it away temporarily; this can open up opportunities to make a dent with your short-range pieces, which can then open up lines for your Lion to do some serious damage. Your opponent will be looking to do the same, of course, so don’t let their advancing army set up a beachhead for their Lion!

- Don’t forget about defence! While hunting the enemy King and/or Prince, don’t forget to maintain suitable defences around your King position. Many players keep their Side Movers on the third and fourth ranks — this sets up a two-rank barrier that even the Lion finds difficult to cross. Leaving a couple of Rooks behind those pieces provides a further deterrent for invading enemy forces.

The Endgame

The endgame of Chu Shogi is a much more open affair than the middlegame — both players’ defences have given way to some extent, and many pieces have been swept off the board. Long-range pieces are flitting dangerously around the more open board, many more pieces are able to promote safely, and victory might be in sight for one of the players.

- Make use of your Gold Generals and Drunk Elephant. Gold Generals can now be advanced in the endgame, preparing to promote to much more dangerous Rooks. Your Drunk Elephant, if needed, can advance into the promotion zone to become a Crown Prince, giving you another bit of insurance in case your King comes under threat.

- Advance your Lion on the enemy King. Your Lion is absolutely devastating in the endgame when backed up with some other pieces. Even if your opponent has created a strong defensive castle structure — to be covered in the next article — a few sacrificed pieces can open up holes in that structure that your Lion can exploit. In your hunger for victory, just be careful not to leave your Lion too exposed, or your opponent may harass it away or even capture it!

- Take advantage of strong promotions. If you’ve managed to keep your Phoenix and Kirin alive, now’s the time to bring them forward! They move a bit awkwardly, but they promote to Free King and Lion, and having extras of those pieces is always extremely useful. You may also have Horned Falcons and Soaring Eagles or other strong pieces available through promotions, which can do severe damage to your opponent’s remaining defences.

With these basic tips in mind, you should be able to get a handle on the general flow of a Chu Shogi battle once you have a few games under your belt. There’s some good information out there online if you want to take your game further — get in touch with Angela Hodges to buy PDF copies of the Middle Shogi Manual and the back issues of Shogi Magazine, which contain a series of useful articles on the game by R. Wayne Schmittberger. Even if you can’t read Japanese, Google Translating the Chu Shogi Renmei website may be useful — there are a number of instructive articles there, as well as checkmate puzzles and complete game records for both historical and recent high-level matches.

Why should I play Chu Shogi?

You may have looked through this article and thought to yourself — why learn all this? Isn’t this game just a more complicated, slower version of Shogi? Why not just learn Shogi instead, a game with millions of players around the globe?

Ultimately, yes, it’s a complex game, and there’s quite a bit to learn at first. But Chu Shogi offers a very different experience from the typical Chess/Shogi game — whereas those games feel like very abstracted skirmishes between two squadrons of troops, Chu Shogi feels like a war. A strategic approach is vital, because right from the start you’ll be making very consequential decisions about where to concentrate your strength, where and when to attack, and how best to execute your devious plans. All the while, the Lions are stalking the board, scaring other pieces into submission, and offering new tactical situations you can’t find in any game of Chess or Shogi.

Even if you’re not a Chess or Shogi player, I recommend trying Chu Shogi at least once or twice — it’s an incredibly rich game, and could easily turn out to be your ‘lifestyle’ game. If you’re a Chess player, Chu Shogi will be like entering a totally different universe — the balance between tactics and strategy is massively shifted toward strategy, the board is filled with pieces that behave very differently from anything in Chess, and the board is so large that it feels like playing three games of Chess at once. If you’re a Go player — well, Go is hard, so you’ve already got a lot on your plate, but as a fan of a highly strategic game you may find Chu Shogi a particularly compelling take on the Chess genre.

Finally, for you Shogi players, I certainly recommend you keep playing Shogi, as it’s a fantastic game. But playing Chu Shogi can certainly pay dividends for your Shogi game, as well as being extremely good fun on its own terms. If you don’t believe me, then at least you should believe Oyama Yasuharu, legendary Shogi player and 15th Meijin, who was an outspoken advocate for Chu Shogi:

“Ever since I was small I have often played Chu Shogi. My cautious and tenacious Shogi style is probably due to the influence it has had. I believe the reason I think, above all, about improving the cohesion of my pieces, is that I have played Chu Shogi.”

Next steps

So, in closing, I hope this post encourages a few of you out there to give Chu Shogi a try. You can play in live games via the 81Dojo client linked on the Chu Shogi Renmei website, via PBEM on Richard’s PBEM Server or Game Courier, or with physical sets produced by Angela Hodges.

If you’d rather practice against AI opponents, you can play in your web browser via the Dagaz Project — scroll down to ‘Shogi Family’ and you’ll see Chu Shogi, Dai Shogi, and loads of other variants too. If you want a really strong opponent, you can download the WinBoard Shogi Variants Package, which includes HaChu, a computer engine designed specifically to play Chu Shogi (it also plays a mean game of Sho Shogi and Dai Shogi). Apparently HaChu can play a pretty great game of Tenjiku Shogi nowadays too, although this version is not yet released — when it is, you’ll want to download WinBoard Alien Edition to play the larger Shogi variants.

Anyway, please pick one of those options and give Chu Shogi a go — it may take a game or two to sink in, but if nothing else I’m sure you’ll understand how this game managed to survive for 600 years, even in the face of the massive popularity of modern Shogi. You may even find it becomes an all-time favourite, as it has for me.

Even better, once you learn Chu Shogi you can easily pick up the larger Shogi variants — you could learn Dai Shogi in a few minutes, and Tenjiku Shogi in an afternoon. I’ll be covering both these games in later posts, too, including a little piece on why Dai Shogi is more than just Chu Shogi’s older, slower big brother. Tenjiku will speak for itself — that game is like nothing else out there and has a deservedly strong reputation.

In future instalments of this Chu Shogi series I’ll cover more detailed tips for Chu Shogi, including building castles for defense and developing checkmating attacks. I’ll also fully annotate a game of Chu Shogi, talking through the moves and hopefully giving you more insight into the strategic depths this game has to offer.

Thank you Eric, this a very accurate and detailed article. I also enjoy the strategic element of the game, and indeed it feels like a full-scaled war.

Thank you very much for your kind comment. I’m soon going to post a second artlcle with further strategic tips I have gathered together from Chu Shogi materials I have accumulated over the years; I hope you will enjoy that one too. If I make a mistake somewhere, please don’t hesitate to tell me 🙂 While writing these articles I hope to improve my knowledge of Chu Shogi, so I’m happy to receive any critiques.

[…] on from my previous article on Chu Shogi, this time I’d like to get into a bit more detail about attack and defence strategies. My […]

[…] on from my previous two posts about Chu Shogi (Part I, Part II), I plan to provide a full annotated Chu Shogi game for you. This is still in the works, […]

[…] enormous games extend Shogi out from its normal 9×9 board with 20 pieces per player, up to Chu Shogi (12×12 with 46 pieces per player) and Dai Shogi (15×15 and 65 pieces per player), then […]

[…] recommended 12×12 Chess variants: Chu Shogi (the best 12×12 Chess-type game, period), Gross Chess (mix of Grand Chess, Omega and Asian […]

[…] in three sizes — Sho Shogi on a 9×9 board (Small Shogi, which became modern Shogi), Chu Shogi (Middle Shogi) on a 12×12 board, and Dai Shogi (Large Shogi) on a 15×15 board. At […]

[…] form of the Lion in Dai Dai Shogi and Maka Dai Dai Shogi. Many of you will remember the Lion from Chu Shogi, where this unique and powerful piece dominates the board; for those new to these games, […]

[…] powerful Lion pieces — Tenjiku includes all the pieces present in Chu Shogi including the remarkable Lion, which may move and capture twice in a turn. In Tenjiku the Lion […]

[…] that I consider Shogi one of the finest games ever created, surpassed only by its larger cousin Chu Shogi, which I believe to be the greatest traditional Chess-like game on the planet. As I’ve […]

Hi Dr. Silverman,

How long is a well played, if not professional, game of Chu shogi? 300+ moves is a hell of a game length. It certainly seems more interesting than shogi if it can be believed. The emphasis on strategy I think is what tips the scales. However not sure I’d be willing to get seriously into if most games were 4 or more hours. In large part because I can’t make that kind of time.

T0afer

Hi there! Hard to say, to be honest, in that my games are competent, at best 🙂 Realistically you’d probably be playing in a PBEM style anyway, since that’s how most people play currently.

If you were to play over the board, games are about as long as a game of Go, in terms of the number of moves, so I’d say if you can fit Go in your schedule then Chu Shogi would be about the same.

That’s great news. Go is just about as long as I can manage on saturdays. I don’t mind going longer, but everyone else does and Go seems to be the extreme limit on people who like abstracts but aren’t lifers so to speak.

I wonder if I can petition Lishogi to try adding it as a variant.

Also, I know over the board is trickier but are there Chu shogi pieces you can buy do you know?

The people at https://github.com/WandererXII/lishogi/issues/472 are making a new open-source online server for Shogi and its variants, and I think that they would really appreciate some clarification on repetition rules. The Japanese Chu Shogi Association has the following rule on its site: “二.千日手は、仕掛けた側が別の手を指さなくてはいけません。(本将棋では引き分けとなりますが、中将棋では指し直すことと定められています。ただし、これはその時代によって検討が重ねられていくべき部分でもあり、今後どのように変更されるかは分かりません)”, roughly translating to “All repetitions are illegal, regardless of checking, attacking, or passing. If the same board position repeats due to a repetition, then the player that started the repetition sequence must change their move.”, (translated by ToriethePanda) which seems to contradict the repetition rule you have given. Have the rules changed since you wrote this article?